The Manila-Madras Connection and the 1762 British Invasion of Spanish-ruled Philippines

Exhibit Description

In 1913, H.D. Love, in the now classic Vestiges of Old Madras summarily dismissed the British occupation of Manila from 1762-64 as a barren conquest. Love continued to say that there were only two results of the Manila expedition as far as Madras was concerned: "the erection of a Manila Trophy at Fort St. George, and the addition of a set of volumes to the Government records. 1 More than a hundred years later, this comment, despite its trifling intent, points us towards two sets of material remnants from this faint historical link between the two fort cities of Madras and Manila in the mid-18th century.

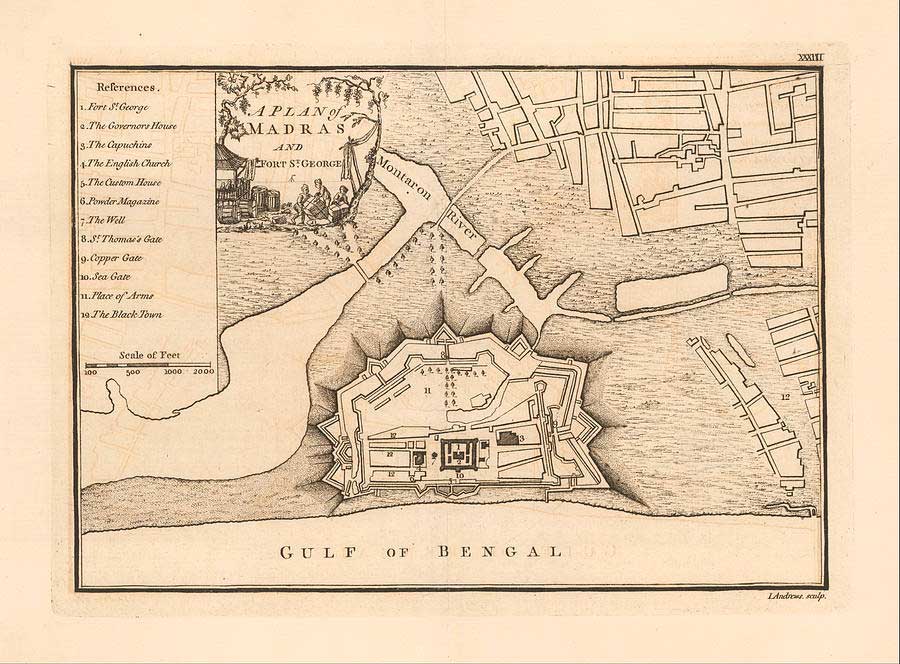

The most obvious place to begin the search for these historical cues from the British occupation of Manila in India would be Fort St George within the city of Chennai. On August 20, 1639, the East India Company secured a land grant along the southeastern coast of the Indian subcontinent for their trade operations. They established the city and port of Madras (renamed Chennai in 1996) and erected Fort St. George, also known as White Town, a year later.

Back in 1762, Madras was the base from which both the British and the East India Company forces embarked on their way to invade Manila. It was also the route of passage on the way back to Great Britain when some of the ships under William Draper and Samuel Cornish left a few months after the successful occupation of Manila and Cavite. Eventually, Madras would also be the point of return when the rest of the British ships sailed out of Spanish-ruled Philippine waters after the signing of the 1763 Treaty of Paris that ended the Seven Years War.

Historically, it was within the walls of Fort St George that both the archives and the war trophy were kept. The Fort Museum is a repository of many relics of the Raj era, including weapons, period uniforms, medals, uniforms and other artefacts from England, Scotland, France and India dating back to the colonial period. In 1851 however, various materials were moved out of Fort St George and were deposited at a newly built Government Museum Complex on Pantheon Road in Egmore. With the independence of India from the British in 1947, more changes occurred. The Fort was turned into the administrative headquarters for the legislative assembly of the Tamil Nadu state. And while many structures built by the British remain - - like St Mary's Church (the oldest Anglican church in India) the rotunda, Clive's House and the graves of former EIC officials --most of the original buildings have been repurposed. The arsenal which once displayed the Manila trophy has now been converted into barracks for the Indian Armed Forces.

The Manila Records

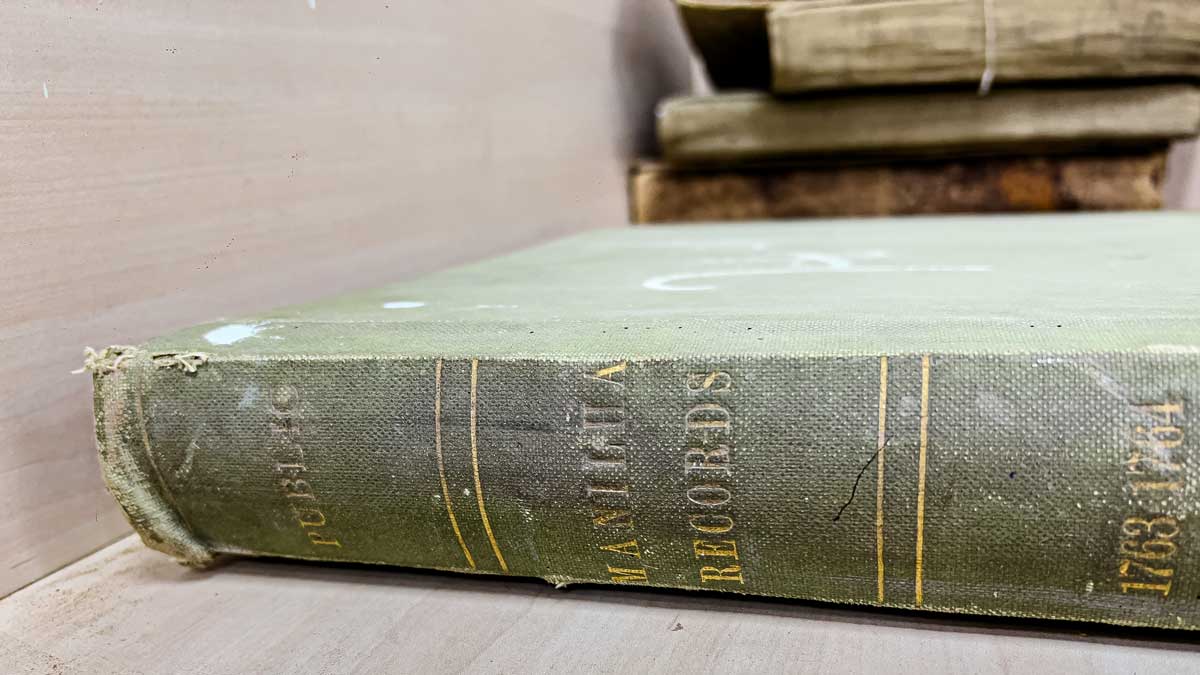

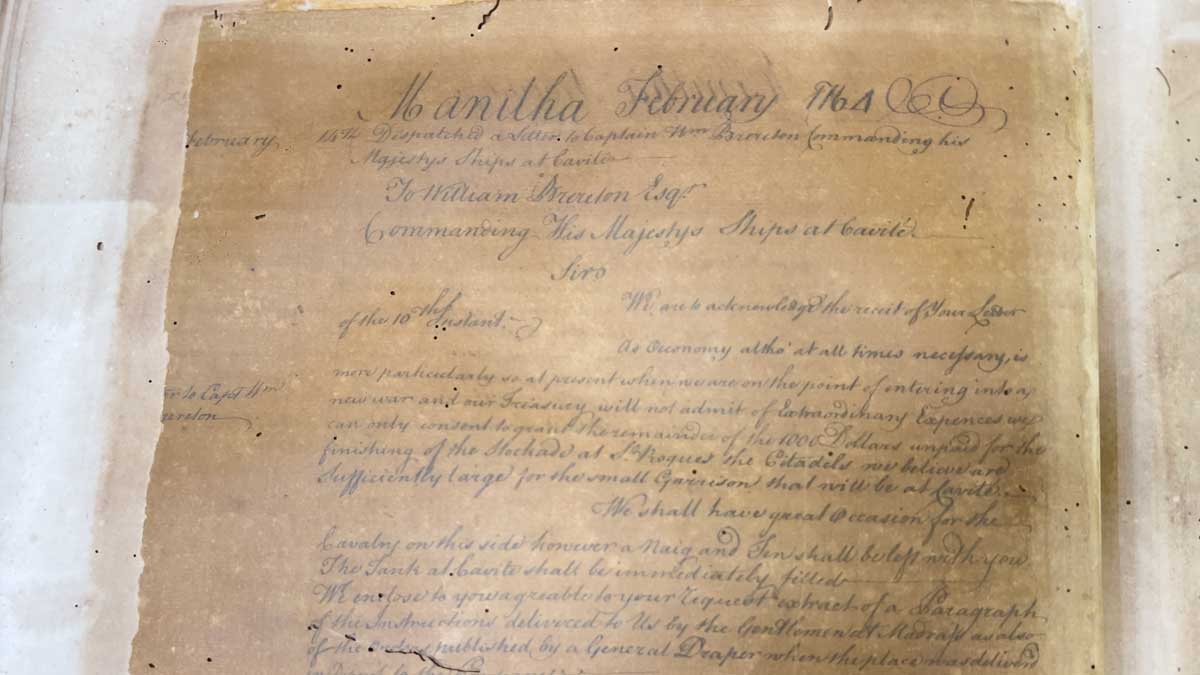

The government records that HD Love mentions is the addition of several volumes to the massive, chronologically arranged "Records of Fort St George," a compendium of memos, letters and proclamations that were produced and compiled by the EIC and the British government up until the late 19th century. The Manila Records within this archive comprise of original manuscripts bound in a series of volumes on the "Diary and Consultations of the Deputy Governor and Council of Manilha" under the British occupation and also a "number of letters written from Manilha to the Court of Directors and to the President and Council of Fort St. George." The original manuscripts were later transcribed, typescripted and reprinted into a series entitled the "Manilha Consultations" first published in May 1940 by the curator of the Madras Records Office.

There is a bit of confusion about the actual number of volumes that the typescripted manuscripts that the Madras Records office finally produced. According to its Preparatory Note, Volume 1 contains the "Proceedings of the President and Council of Manilha from 23rd September 1762 to 28th December 1762, and is the first in the series." It is followed by several other volumes published incrementally through 1943. According to a letter written to Ifor B Powell in 1963, the Madras Record Office Publications noted that based on the manuscripts kept at the Archives, the typescripts would be printed in 11 volumes. Volume 1- 6, 9/9A and 10 had been printed but that Volume 7 was a duplicate of Volume 5 and 6 and that there was no Volume 8. In 1963, they also said that the last volume (Volume 11) had not yet been printed. 3 .

The original manuscripts remain at the Tamil Nadu State Archives Office today. It is difficult to physically access these materials, but by following a rather involved process, (letters of recommendation from your institution and from one's embassy, various paper forms to fill, no online catalogue and a multi-day wait for any of the requested materials to come) researchers can get to see them. And while the publication of the Manilha Consultations is a great resource, comparing the type scripts with the original hand does yield some errors and elisions. There are also a few more relevant materials in the general records that the editors have not picked out to include in the Manila Records.

Trophies of War

The British are notorious for collecting war trophies, commemorating their military victories with displays of captured arms and standards. Aside from common looting in warfare, trophies are taken for their nationalist connotations—objects valued for their extra-literal significance rather than their worth in material capital. During the British occupation of Manila, the extent of the looting and pillaging of the city has become infamous. Among the spoils, there were specific efforts to seize symbolic artefacts of conquest for imperial display.

The more well known trophy from the British invasion are the nine Spanish colours that the British took and brought to London by William Draper. An interesting entry in the Cambridge Chronicle documents the quasi-religious undertones of this British display of power against Spain:

On Wednesday, 4 May 1763, ‘the Spanish standards taken at Manilla by General Draper, late fellow, were carried in procession to King's College chapel by the scholars of the college. A Te Deum was sung, and the Rev. W. Barford, fellow and public orator, delivered a Latin oration. The flags were placed on either side of the altar-rails, but were afterwards removed to the organ-screen’.

—Cambridge Chronicle 7 May, 1763 and later 15 Oct. 1763

Afterwards however, these Spanish flags were stored away and towards the end of the nineteenth century, re-discovered and placed on display under glass but then again later on discarded.

Aside from the Spanish flags, the lesser known set of war trophies from Manila were brought to Madras and installed, at least initially, at Fort St George. This consisted of an "escudo de armas," a set of two Spanish cannons and several pieces of Spanish helmets and breastplates. We don't know why these were not brought to London like the Spanish colours. Perhaps these were the EIC's share of commemorative booty and a memorial to the military prowess of what technically was a private trading company. Again from H.D. Love:

Tradition asserts that the trophy, now dismantled, was placed near the Arsenal gates; but as the Arsenal was not begun until 1770, the Artillery Park is perhaps indicated. The trophy was flanked by two fine Spanish cannons dating from the beginning of the seventeenth century. These guns, with others of Danish and Mysore origin, occupied until lately a position on the parade-ground. They are now in the Madras Museum, where fragments of the trophy itself are stored though not exhibited. 2

The Escudo de Armas

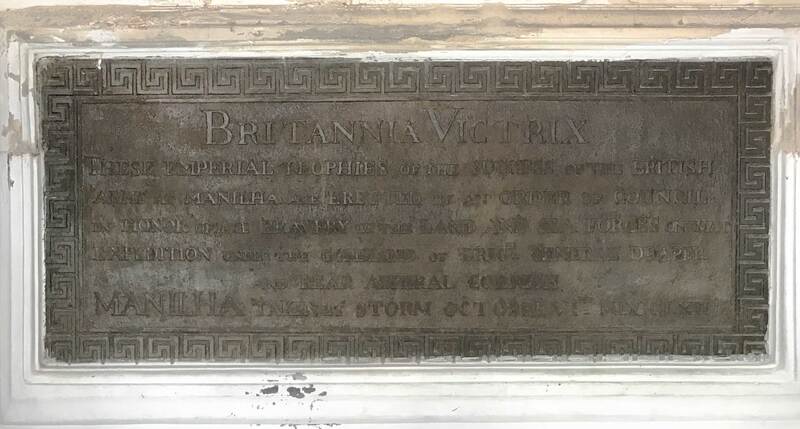

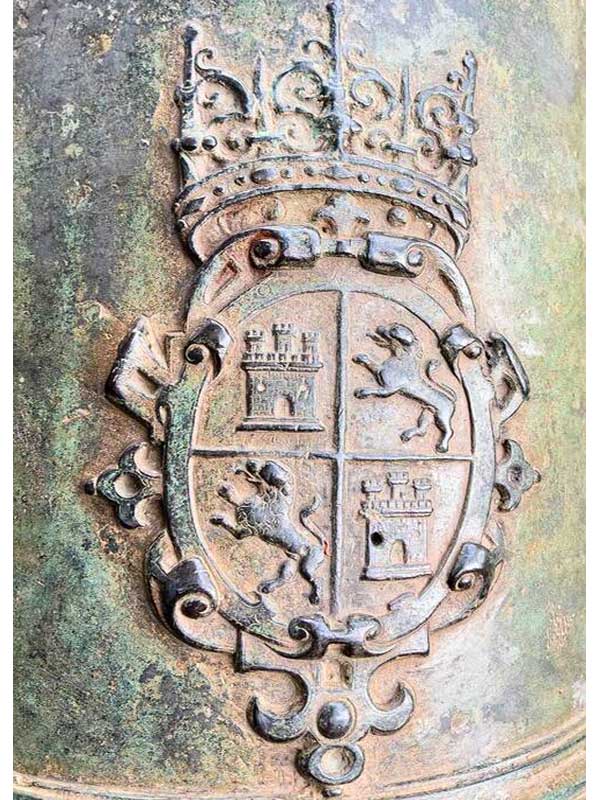

Today, the escudo de armas is displayed in the War Trophy room at the Government Museum of Chennai. Now shown by itself (without the flanking cannons) it is wedged between two wooden vitrines crammed with all sorts of weaponry. A bronze plaque (most likely made at the Arsenal in Fort St George) is fixed to the wall underneath the Escudo and announces its commemorative slant:

Britannia Victrix

These imperial trophies of the success of the British Arms at Manilha are erected by an order of Council in honor of the bravery of the land and sea forces on that Expedition under the command of Brig(r) General Draper and Rear Admiral Cornish Manilha taken by storm October VI (th) MDCCLXII (October 6th 1762)

The escudo itself is a mid relief sculpture depicting Spanish coat-of-arms .The escudo is classified as a heraldic lintel piece, usually mounted on the walls or roofs of palaces, government buildings, or on the lintels of gates to fort complexes. Museum records indicate that the escudo was "taken from the gates of Manila during the expedition in 1762 when the town was captured by Madras troops."

The significance of the elements in the coat of arms gives clues to the manufacture date and provenience of the escudo, but a lot more research needs to be done . From personal communication with Paolo Paddeu, an Italian Researcher and Vexillologist and one of the administrators of the Kapisanan ng Vexilolohiyang Pilipino, the escudo likely represents a Spanish military coat of arms. This naval or military provenance is reflected in the numerous weapons that surround the shield - including cannons and cannonballs, spears, pikes, drums and flags. It is not a "minor" royal coat of arms of Spain because it presents particular elements that have not been seen in relation to the Spanish royal escudos but seems to be a hybrid between the military coat of arms of a high officer and that of the kingdom of Spain.

Some Spanish coats of arms of the "Teniente General" for example often have weapons, flags and various symbols but do not generally exhibit the elements of the Royal Kingdom's coat of arms in the shield. All this points to the possibility that this could have been the coat of arms of the Philippine Governor General and might have been installed in the Ayuntamiento or the Governor General's building within the walls of Intramuros.

Other elements that Mr Paddeu points out are the two stylized lions (symbol of Spain) placed as supports on the sides of the shield, the lack of the pomegranate symbol that identified Granada and the presence of the "Golden Fleece" symbol and of the "Espiritu" which generally has a dove placed upside down but which in the analyzed coat of arms is instead placed right side up. This anomaly could suggest that the shield was made by some craftsman from Manila, following the indications of the Spanish clients .The presence of the "Espiritu Santo" as a decoration of the Spanish coats of arms is present from the reign of Felipe V up to Carlos III and given the period in which the coat of arms was captured (1762) it can be been conceived in the period of government of Carlos III.

Regalado Trota José (August, 2023) continues the discussion about the dating of this escudo by pointing out that the fleur-de-lis in the centre of the escudo denotes the Bourbon dynasty, which came into power in the first years of the 18th century. He believes that this specific iteration of the coat of arms could have been produced during the time of Fernando de Valdés y Tamón who was appointed governor of the Philippine Islands on August 4, 1729 to July 1739 and who worked on fortifications in Manila and many other Philippine islands. The elements of this particular heraldic piece have striking resemblances to the Royal Spanish royal coat of arms for the Palace of the Governor General of the Philippines from that period. Could it be that this was Fernando de Valdés y Tamón unique escudo? As already noted, we cannot be certain when or where this escudo was originally installed - all we know is that it according to the 1854 Madras Museum records, this was taken from the Intramuros by the British in 1762.

In terms of material, museum records say that this piece is made of bronze, but a closer examination points to it being more likely made of hardwood coated with a thick reddish underlayer that has oxidized on the surface. According to Dino Carlo S. Santos, Supervising Historic Sites Development Officer for the Intramuros Administration, the red undercoating is most likely "clay bole" - used on hardwood before it is gilded. As was done in the Philippines, a burnishing tool buffs the malleable layer of clay bole underneath the surface coating, before gold leaf is applied. Some interesting parallels between the practice of wood carving and gilding of religious scupltures in the Philippines during that period could be made with further material and chemical analysis of the escudo. This type of material also lends to a more logical placement of the escudo orignally -- for if it were indeed taken from one of the "gates" of the Intramuros as recorded in the Museum records, the hardwood material of which the artefact is made, if exposed to atmospheric agents such as rain, sun, wind would have suffered damage in a short time and deteriorated. So unlike the carved stone heraldic lintel pieces that are currently installed above some of the gates in Intramuros, this escudo could have been located inside some building, or located above the entrance to the Ayuntamiento.

The Spanish Cannons

In addition to the escudo, the Madras war trophy also consisted of two Spanish cannons flanking it on each side. Nicknamed San Pedro and San Lorenzo, these 17th c Spanish Cannons are separately mounted on a four wheeled carriage with the following inscription: "This gun is believed to have been taken at Manilla by Draper in the year 1762 AD" Museum curators believe that this label could have been added at a later date when the cannons were moved out of Fort St George.

A visual inspection of the canon shows that the canon has an earlier version of the coat of arms of Spain and another smaller and older inscription in Spanish that gives a clue regarding the canon's provenience.The very faded text seems to indicate that the canon was cast in 1604 at "Chapulrepeque," by order of Don Juan of Mendoza and Luna, Marquess of Montesclaros." The other cannon named San Lorenzo, a few inches shorter in length, also bears the same arms of Spain and has a similar inscription of its provenience.

The Spanish Armouries

The final cache of trophies from the British occupation of Manila are some captured Spanish helmets and body shields. According to HD Love, "480 pieces of brass ordnance, captured at Manila," came with the two Spanish cannons and now a few pieces of these brass helmets and shields are also displayed in a rather crowded and poorly labeled cabinet at the Government Museum in Chennai. The museum label points to the provenience of these Spanish armouries:

"When Philippines was under the rule of Spain, British attempted to capture Philippines in AD 1762, leading to a battle between the British and the Spanish in and around Manila, the capital of the Philippines. The British won at the end, leading to a very brief British occupation of Manila between 1762-1764. The iron helmets and breastplates exhibited in the showcase were acquired by the British from the Spanish army after their victory in the Battle of Manila (1762. "

And there it rests its case.

Ultimately, the Manila trophies in Madras serve as witnesses to the complexities of the history of empires. When Spanish official Francisco Leandro Viana, who was in Manila during the 20-month occupation, explained to King Charles III in 1765 that "the British did not own any land beyond the range of their cannons; the conquest of the Philippines was only imaginary," Spain would continue to contest the narrative of British victory over Spanish-ruled Philippines. The existence and display of these war trophies can in one sense be seen as mere tokens of British imperial bluster.

Back in the Philippines, this war trophy is still only an emblem of an empire long forced out of Philippine territory. The gesture of aggression meant in the taking of these specific objects no longer resonates with many. But perhaps the escudo can be studied for its material significance in relation to processes of making from that period. It could also be used as a history lesson in the permutations of Philippine vexillology throughout its long history of multiple colonizations.. As the objects themselves remain in Madras, a few centuries and an ocean away from cultural and historical relevance, what is left behind is just the echo of a long-ago conflict between Spain, Britain, and The East India Company played out in a brutal game on land caught in between the crossfires of inter-imperial warfare and expansionist greed.

________________

Footnotes

1 Love, H. D. (1913). Vestiges of Old Madras, 1640-1800: Traced from the East India Company's Records Preserved at Fort St. George and the India Office, and from Other Sources. United Kingdom: J. Murray. pp. n630

2 ibid., p. n630

3 The entire set collected by Ifor B Powell has been digitized and deposited as open access material at Digital Filipiniana at SOAS. This letter for Powell has been inserted as loose paper into Volume 1 of the series.