Notes from the Field: A Blaan Kastulen and the Archive as a Site of Engagement

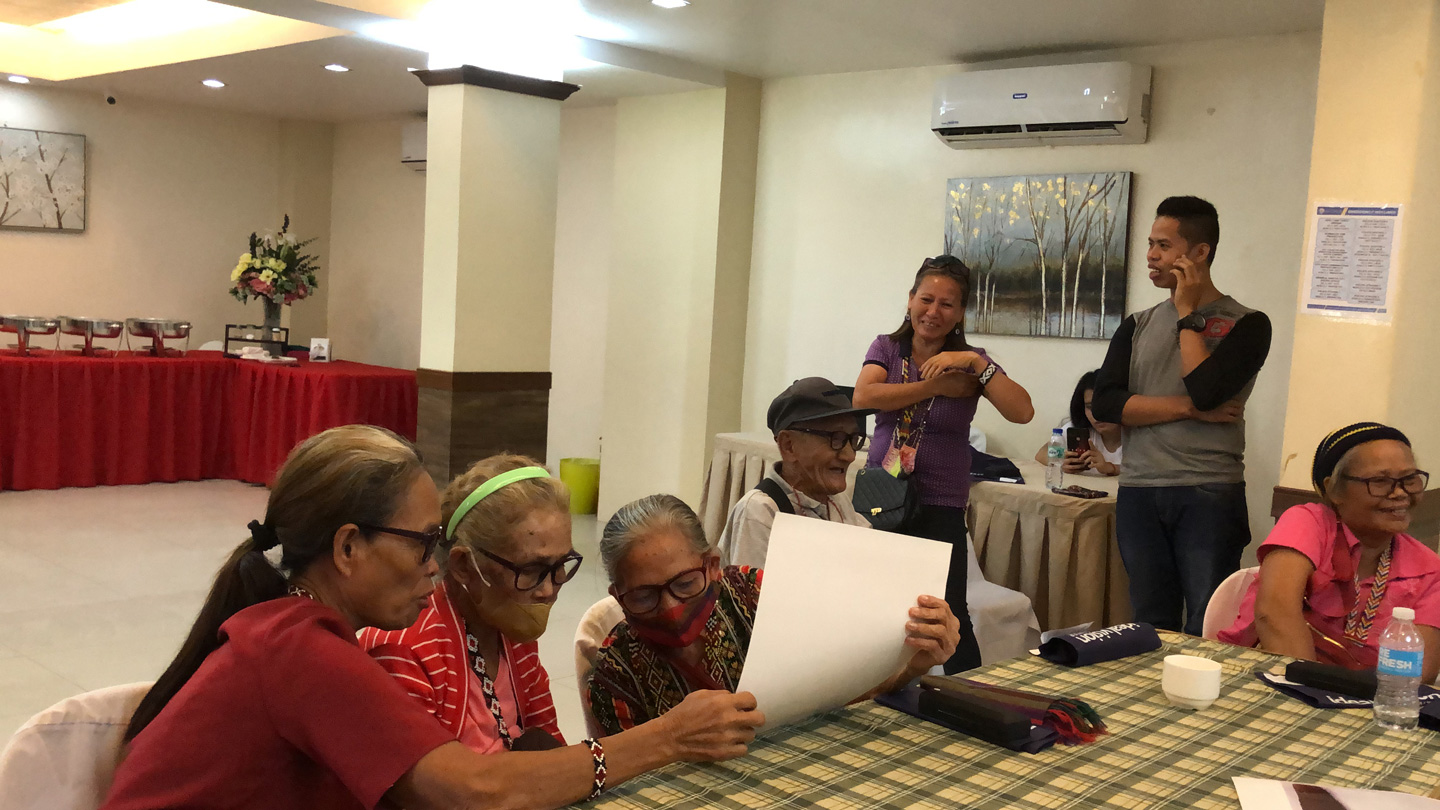

Bai Deborah M. Ganton,Bai Andrea “Diya” Martin Lawa, and Bai Estelita Tumandan Bantilan, the Gawad ng Manlilikha ng Bayan examine the photos of Blaan material culture. General Santos City, June 26 2022.

by Cristina Juan and Maribeth Farnazo

Background

When Philippine Studies at SOAS launched the Mapping Project in January 2021, we always knew that all we had was baseline data (still incomplete and growing). Conceptually, the Mapping site was to begin as a global inventory of pre-1960 Philippine material culture in overseas collections, and that it would increasingly grow towards becoming a "site for engagement." We have been constantly seeking ways to not only create digital access to these materials but to also actively develop grounded ways for accessing and re-valuing Philippine-made objects in these collections.

In October 2021, Marian Pastor Roces introduced me to two very empowered, very eloquent Blaan women over zoom. Arjho Carino Turner is a Blaan from Polomolok, South Cotabato and was the Indigenous Peoples Development Program (IPDP ) Manager of Sarangani Province before she moved to Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Maribeth Farnazo is from Malapatan, Sarangani and became the new IPDP Manager when Arjho left the province at the end of May 2006.

The introduction was a way to start a conversation about what we could do to reconnect the over 4500 Blaan objects in the Mapping Project’s inventory with the Blaan in the Philippines. Our conversations ran through the usual points of discussion on “decolonizing” ethnographic museums -- but this time, all very local, practical and real. The topics ranged from repatriation to derogatory language in object descriptions to provenance, how to make the objects more findable in the database or the loss of knowledge systems and contexts in relation to memory. At a certain point, we began to see the limits of online chatting and my hare-brained ideas of doing a zoom meeting with the Blaan elders and do "photo-elicitation" online. Maribeth insisted that we needed to build relationships, that I should go to General Santos City and meet Maribeth's Blaan relatives and friends. Eat together, mostly chat around the images and not do a formal "workshop" She also insisted that I should at least print the images from the Mapping site and not just show it online -- to make them poster-sized and good quality so I could leave the posters behind and the Blaan could have something tangible - something to put up in village exhibits or in IP schools. When these clear parameters were set, the idea for a Blaan Kastulen or "Conversation" became clear.

Preparations

a) Funding

In May 2022, and at just the right time, SOAS sent out a call for micro-scale proposals from the UKRI participatory research fund. I submitted a proposal for "A Blaan Kastulen: a digital repatriation project for participatory research and the co-production of knowledge with the Blaan Community of South Central Mindanao" and got the grant the following week. It was wonderful - especially given the fact that the Mapping project does not have sustainable funding, and most of the In conversation schemes we have are done with volunteered resources and people. The grant was a lifesaver. It allowed me for example, to invite Marian Pastor Roces to come with me to General Santos City from Manila.

b) Materials

Only 1500 objects had photos out of the 4980 aggregated Blaan materials in the Mapping project inventory. I spoke with Jaime Kelly, Head of Anthropology Collections and Collections Manage for the Field Museum in Chicago and asked if he could very quickly take photos of the Blaan material in their collection. The Field Museum has 577 Blaan objects but only about 90 have photos. Time was short and I needed to get the high resolution posters that Beth requested. Working with Fay Cooper Cole’s card catalogs from the Robert Cummings Expedition to `South Central Mindanao from 1909-1911, Maribeth and I picked representative objects, sent the list over to the Field Museum and hoped that Jaime would see it through. He did. He even got close up photos which would later be of great interest to the Blaan elders. He said we could do what we wanted with the photos. It seemed that everything was set.

c) Consent

Maribeth did all the planning for the week-long event. More importantly, she worked to get consent to engage with the Blaan Indigenous People in Sarangani Province from the Indigenous Political Structure (IPS) and National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP). She asked me to write various letters addressed to the Municipal Mayor of General Santos City, the Provincial Tribal Chieftain of Sarangani Province, and the Provincial Director of the National Commission on IndigenousPeoples (NCIP). Beth facilitated a meeting with these governing bodies and got a signed consent resolution dated June 24, 2022, (A Resolution Manifesting co-ownership of the Mapping Research Project-Based in SOAS University of London and to Allow Bai Maribeth B. Farnazo, Research Fellow to contact interested participants in the Indigenous Cultural Communities to attend and contribute to the Discussion Workshop - full copy here). The IPRA (Indigenous Peoples Rights Act 1997) is pretty clear about the mechanism for getting permission to do research with the indigenous peoples of the Philippines. Maribeth's long and valued work with the IPs in the area, along with the trust the Council had for her as a Blaan who wanted to do good for the IPs, mitigated what would have been a very long and complicated process.

Building Relationships

Marian and I traveled to General Santos City on the week of the 26th of June 2022, where Beth met us with a full week's schedule of travel around south central Mindanao. Right out of the airport, we went straight to Upper Lasang, Malapatan where Marian would reunite with a long-time friend Bai Estelita Tumandan Bantilan, the Gawad ng Manlilikha ng Bayan GAMABA Awardee for weaving traditional ‘igem’ (mats). Marian calls her Princess.

We also had an opportunity to meet several other women mat weavers. One by one, they showed us their handwoven mats- highly skilled work which embodied individual design and their own distinctive turns of hand in their mat-making.

I was able to purchase the handiwork of Iris, one of the weavers who studied under Bai Estelita in the Malapatan School of Living Traditions. I was struck by the fact that if I had not met her, I would have brought home another unnamed "folk craft." She had written her name on the left-hand corner of the wrong side of the mat. I would have missed her name entirely. In the video, Iris speaks in Blaan and tells me that it took her two weeks to weave the "lining" of the mat, and another two weeks to weave the top part.

THE KASTULEN (Conversation in Blaan)

The more structured Blaan Kastulen was arranged for June 27-28 in a simple hotel in General Santos City. Staying overnight in one place would be more convenient for the elders who were coming from five remote villages of Maasim, Malungon, Alabel, Malapatan, and Glan. There was a lot of eating and laughter in the two-day meeting. Dyisi Salway, wrote very detailed documentation here.

After the two-day event, we continued to meet other source communities and stakeholders in South Central Mindanao. As part of the recommendation of the ICC, that similar digital repatriation events could be done with other Indigenous Cultural Communities in the area such as the Bagobo, Tboli, and Tagakaulo, we took the opportunity of doing these initial visits to establish a connection.

Maribeth introduced me to Benjie Manuel, a T'boli and project lead for 'Yê Kumù' – a T'nalak Weaving Center in Lake Sebu. Over a delicious meal, we talked about the weaving center and how a similar conversation around Tboli objects stored in overseas museums might be useful to them. Benjie, who is a Secondary school teacher, was excited to have photos set up in the weaving center, and using the images for materials in their IP secondary and primary school curricula.

We also visited the Lang Dulay Weaving Center to connect with the descendants of the famed Tnalak weaver Lang Dulay who had passed away.

Finally, a visit was made to the Lamlifew Women’s Association. Located in Lamlifew in Barangay Datal Tampal of the town of Malungon in Sarangani Province, the association runs a weaving center and also a Village museum. The museum was initiated by the Lamlifew Tribal Women's Association (LTWA) - the first SEC-registered cultural organization completely initiated and operated by a Philippine indigenous community. It was launched in the Lamlifew Village on November 26, 2008, and today, it is a functioning museum that manages a small but important collection. We spoke with the Blaan who runs the cooperative and asked if they might be interested in putting together a similar Kastulen at Lamlifew.

Action Points and some Take-Aways

a) The direct annotation of twenty-five representational object descriptions that contained derogatory, under-researched, or wrong information in the Field Museum database. These annotations were made directly into the database of the Mapping site with the Blaan elders in real-time. As we made the inputs on the digital platform of the Mapping site, just having the ability to correct these mistakes gave the Blaan a sense of power over their heritage and a sense of ownership and control.

As an example, a global algorithmic change was made in the entire Mapping site of all attributions to the Blaan using spelling variations that are considered derogatory (Bilaan, Bila-an, B’laan). This global change was made after specific requests from the Blaan. (Read the documentation here.) The Blaans in the Kastulen recounted their childhood memories and some very real experiences of racism that were expressed with the way Blaan is pronounced or spelled by people who hold deep antagonisms around the Blaan people. There was a palpable sense of satisfaction when we re-inscribed their collective name. This change affected all other Blaan collections in the Mapping inventory, including the collections at the Field Museum, American Museum of Natural History, Harvard and The Penn Museum.

b) As a site of engagement, the Kastulen became a way to reconnect material culture with the Blaan and their cultural memories. Based on the reflections of some of the elders (see Dyisi Salway's documentation of their reactions here) it was clear that this created a sense of pride and self-identification. For the younger generation who participated in the event, it “developed pride within the Indigenous People seeing the beauty and elegance" of the objects. It was also clear that there were a lot of complex emotional responses to the physical loss of the objects: resentment, nostalgia, sadness mingled with a stoic sense of hopelessness of ever getting these Blaan objects back. There was also this feeling of surprise and gratitude towards the institutions who have kept and preserved these objects, with many commenting on how these institutions could have kept the objects in such perfect condition over a hundred years. Which begged the question that often followed : why would these institutions collect and preserve these objects for such a long time and at such a cost? After telling them that these objects are kept in dark storage rooms and that only one or two out of the thousands of Blaan objects have been put on display, they of course asked for clarification. What are the museums' plans? Are they just keeping these in storage, without any easy access to anyone forever? It was interesting to see their bafflement - an exact mirror of the questions being asked of the relevance of ethnographic museums, especially in a decolonizing networked globalized world. They did thank the Mapping Project for at least letting them know that these precious objects were out there. I made it clear that hopefully, this virtual - digital access that we provided would just be the beginning.

c) A localized application of what meaningful restitution might mean to the Blaan elders at the Kastulen. There was a general agreement that the physical repatriation of the objects was not feasible at this time. We spoke about the complex factors involved in returning objects to source communities - and for the Philippines, where a majority of objects were taken by collectors or academics, and not necessarily from direct looting - the question of where to return or to whom is even more fraught. Would these objects be even considered for repatriation? Would the National Museum in Manila get the objects? Given the lack of specific provenance - which families in the Blaan villages would receive them? Who would take care of them? It was clear that the idea of taking care of these objects and preserving them would be too costly, and that it would become a source of either unwanted responsibility or conflict among the Blaan communities spread across Southern Cotabato.

There were however several requests to ask for more technical specifications to help them in reproducing specific objects they felt were significant. Some of the elders said they could reproduce the objects shown in the photos, but other objects have fallen out of use, and others could not remember how things were made or what they were for. The mat weavers in the group wanted to know more about mat weaving patterns, dyeing techniques, and the materials used. They asked for other objects in the inventory that would use Igem in making other things (e.g they loved this Blaan bag that I showed them).

In The Kastulen, the men were especially intrigued by the feathered headgear, as according to Fulung Fredo, they have not seen this type currently in use. Today, respected leaders among the Blaan put on an otob, a type of headscarf for special occasions, but this practice is seen as coming from the Muslims and not "pure" Blaan. (1) This led to further conversations about recreating the use of the headgear as a mark of cultural distinction among the Blaan in the area. They also appreciated the blow-ups and detailed photos of the insides of the headgear, as they were trying to figure out the material or the way it was woven. The way an object is photographed in museums is for frontal display - but it was interesting how the more technical processes documented in some of the close-ups were highly appreciated. In some sense, and to this local gathering, this and opportunities like these were how they thought would best serve as a reparative course of action by museums. I felt that if there was any programme that museums could do, it was to proactively look for ways to connect the objects with the source communities. To go beyond the obsession over preservation.

d) Institutionally, the Field Museum will be able to mirror the annotated object descriptions in the Mapping site in their own online database. A copy of the documentation will be sent to the Field Museum along with the Blaan request to have Blaan variant spellings changed in the Field Museum’s database.

e) Stability in flux. It is difficult to stabilize methodologies and meaning from out of very local, temporal, and very specific instances of participatory research. From axing the "schedule" of half an afternoon of the "workshop" to go get reading glasses for the elders, to re-allocating the budget towards inviting a ritualist to come -at the last minute-- and do a damsú ( see Dyisi's documentation here). We shifted gears when we began to see that the elders began to feel the need to honour the ancestors who made these objects -and do something to please the spirit of the ancestors by asking permission to use or name the objects which would have belonged to them. Most of all, participatory research needs to grow - and change -with time - at the speed of relationships they say. In many ways, a method like "photo elicitation" only works if it results in non-extractive knowledge and understanding that would ultimately benefit the source community. Choosing to name this exercise as a Conversation has hopefully created a living, breathing site where an archive and lived ethnography can meet.

___