What's On View: The City of Madrid

by Cristina Juan

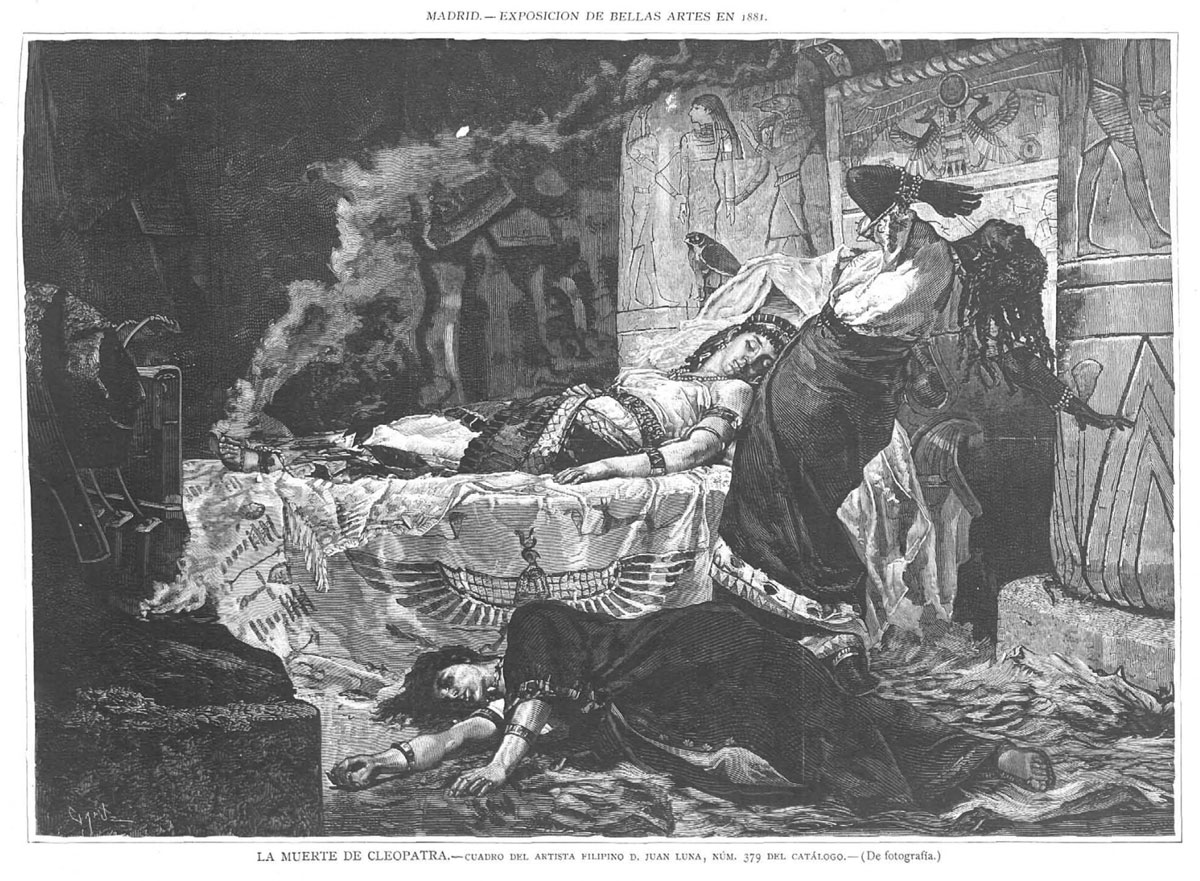

You turn the corner into Room 61- A of Madrid’s Museo del Prado and it is there, waiting to overwhelm you: Juan Luna’s La Muerte de Cleopatra. It has all the hallmarks of a first-rate Luna in his “historical painting” phase: the grand scale, the theatrics, brisk, assured brushwork, luxuriant flesh tones and expressionist contortions very similar to the hand of the Spanish painter and his mentor, Alejo Vera. It won for Luna his first major prize in Europe, a second class medal at the Exposición General de Bellas Artes in Madrid in 1881. It also drew a lot of attention from Spanish art critics. E. Martinez De Velasco reviewed the painting in La Ilustracion Espanola y Americana and called Don Juan Luna "es una esperanza legitima para el arte español contemporáneo" (La Ilustracion Espanola y Americana, 22 June 1881 p. 406).

In a follow up article, the painting was one of the few pieces from the 1881 Exposition that got its own line engraving (30 June 1881 p. 419 ). The magazine captioned the engraving as a “cuadro del artista Filipino,” (an early use of the switch in meaning to Indio), and again reiterated that Luna was indeed the "hope of contemporary Spanish art. (1)

The painting brought the young Filipino painter his first flush of fame and fortune. Because of Cleopatra, the Ayuntamiento de Manila awarded Luna a four-year grant to continue his art studies in Rome. (2) The Spanish government also bought the painting for 5000 pesetas, a significant amount at the time.(3) The administrators of the Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas chose to exhibit it at the Fair., where it was given a honoured place among the Bellas Artes.(4)

But despite La Muerte de Cleopatra’s rather illustrious beginning, it wandered and then languished in different storage facilities for a century - forgotten and virtually inaccessible. Its entombment began when it was first inventoried in the Catálogo Museo de la Trinidad in 1889, Núm. T-155. The Museo was a satellite government facility set up by the Spanish royal family to house pieces that won prizes at the expositions. The Museo de la Trinidad was infamous for leaving many paintings piled up in a manifest state of abandonment. It was eventually closed down with its entire collection distributed to various museums in Spain.

The Cleopatra was transferred and next inventoried in the Catálogo Museo de Arte Moderno, 1899 as Núm. 221. The M.A.M was a national museum dedicated to the art of the 19th and 20th centuries, and existed from 1894 to 1971. When it closed down in 1971, all its collections of nineteenth-century art was transferred to the Prado.

It was only in 1988 - exactly 100 years after its exhibition at the 1887-88 Exposition --that the painting briefly resurfaced. The Prado lent the painting to the Centro Cultural Conde Duque, in Madrid to be a part of a temporary exhibit called Exposiciones Nacionales del Siglo XIX Premios de Pintura (1856-1900). The 4-week exhibit ran from June 6, 1988 to July 7, 1988, and produced a catalog with a brief description of the Cleopatra.

Then 2017 happened and the long-lost Luna painting became a big deal. The National Gallery in Singapore, led by its research and curatorial team, tracked down all the Lunas in Spain and came back with several pieces that would be shown in the ground-breaking Between Worlds: Raden Saleh and Juan Luna. (November 15, 2017 - December 3, 2018). The National Gallery zeroed in on the Cleopatra and spent a considerable amount in restoring the masterpiece. It was one of the central pieces in the show, along with Luna's Espana y Filipina and Les Ignores.

When the piece went back to the Prado in 2018, the museum curators picked up the now-resplendent Luna, and, coinciding with its extensive renovation and thematic recalibration of its 19th Century Painting gallery, decided to include the Cleopatra in the room's permanent display. (5)

****

Esteban Villanueva y Vinarao also at the Prado

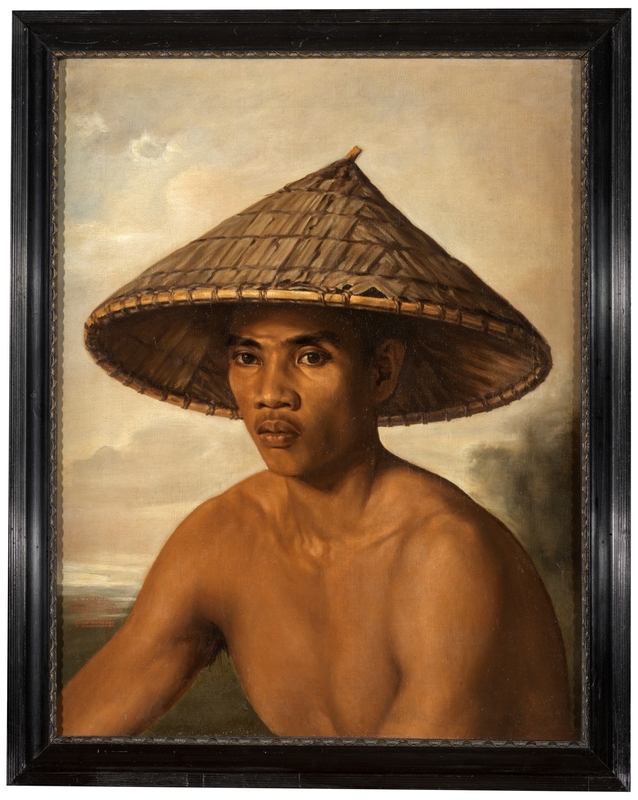

Aside from the spectacular Luna, the Prado's permanent collection also includes two other paintings by Esteban Villanueva y Vinarao. Born in Manila ca. 1859, he studied in Madrid between 1875 and 1878 and eventually retired and died in Alicante, Spain in 1920.

He trained under Agustín Sáez in Manila and at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. He has seven other portraits of Filipinos in the collection of the Prado, making him the earliest and most well-represented Filipino painter at the museum. Interestingly, the 2 paintings were deposited/loaned by Royal Order to the City Hall of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria in 1913, and were only taken back to the Prado, again by a Royal Order in January 2021. The 2 paintings went into permanent display from July of 2021.

The juxtaposition of the two Villanuevas with the Luna is an interesting curatorial choice. The caption, lodged in between the 3 paintings, says:

"In an overseas context, painters born in the Philippines created a type of work which reflects an interest in the characteristics of their own culture through its depiction of local people and landscapes. Many of these works were included in the Philippines Exhibition held in Madrid in 1887.."

Previously, in its description of the Fin de Siècle, the same caption speaks of the decline of history painting and the rise of naturalism and social themes - alluding to how artists at the end of the 19th c depicted a wide range of subjects, including in many cases, social critique. It is not clear which part of the entire caption refers to which paintings. Much can be said about the choice of words, or the unfortunate (or perhaps clever) colonial collocation, but in a real sense, the three paintings on permanent display at the Prado is indeed a statistical anomaly, and a welcome surprise.

****

The Museo Nacional de Antropología

Just a 10-minute walk down Paseo del Prado Madrid's Anthropology Museum is one of the world's top contenders for the most number of Philippine material culture on permanent display. Ringing it in at 322 objects and given a prominent place on almost the entire ground floor, the Philippine section of the museum displays a wide range of material -- all remnants from Madrid's Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas in 1887.

The permanent display was installed in the 1980's, and has since then, been a go-to place for viewing exquisite piña or models in silver, but also souvenir kitsch made exclusively for the exposition.

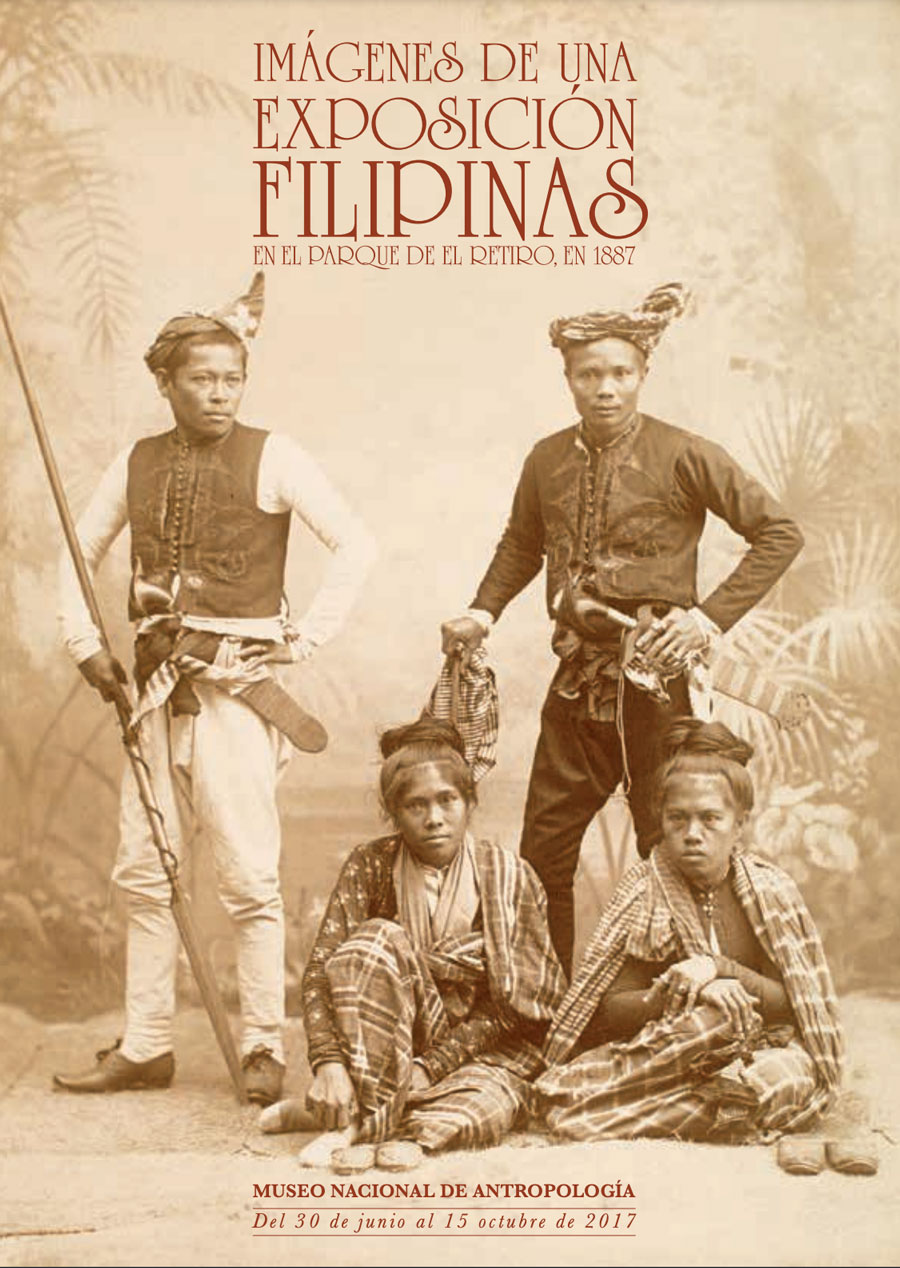

The catalog of the 2017 Exhibit. This is a downloadadble copy.

It also has a good selection of wood sculptures on permanent loan from the Prado (also from the 1887 Exposition). This catalogue has an inventory of all the pieces displayed at the exposition, including very granular proveniences of Philippine towns and villages - including names of people who sent items over to Madrid (over 3,500 Philippine materials from the Exposition remain in storage).

In 2017, Imágenes de una Exposición Filipinas en el parque de El Retiro en 1887 exhibited the photographs taken during the exposition, and placed them side by side with the objects. The six-month temporary exhibit ended in November of 2017, but many of the photos became part of the permanent display in the "Philippine Room."

There is much that can be said of the labels for each of the vitrines, and there is a real need to annotate the captions and curatorial categories of the permanent exhibit. The MPMC project is currently working with the Museo to add the data to the Mapping site, and hopefully begin to annotate or at least give further access to the data for knowledge correction and exchange.

****

Other Pieces Scattered in Madrid

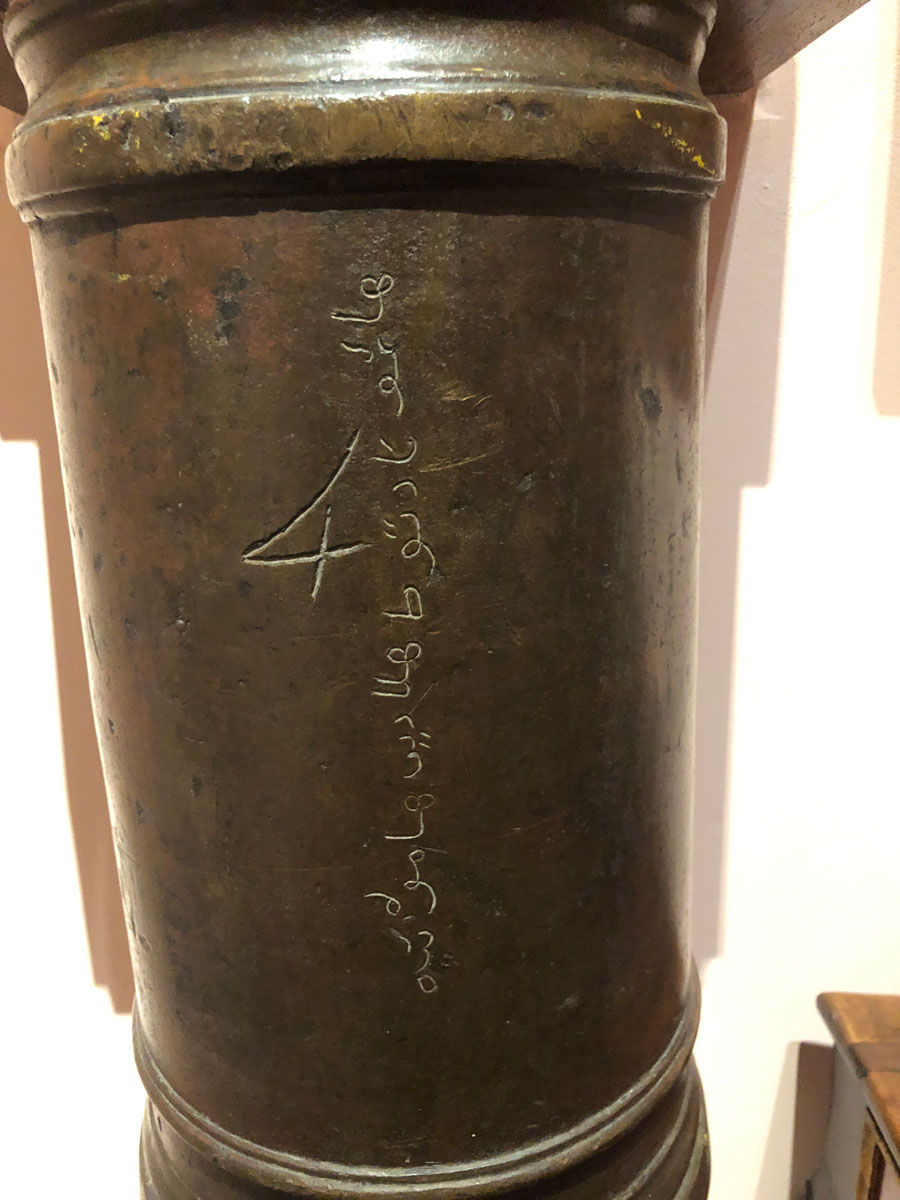

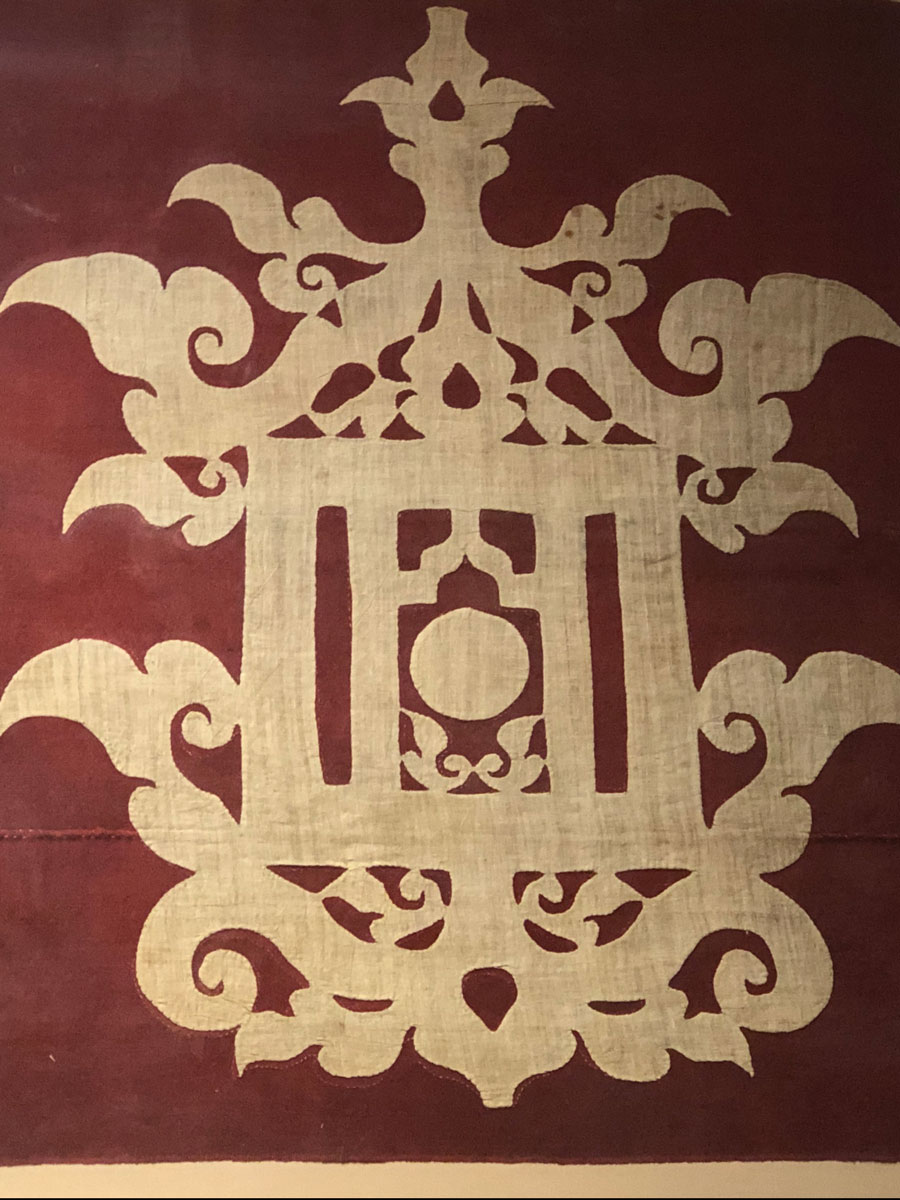

The Museo Naval has more than 300 objects from the Philippines, but only a very few are on permanent display. Striking ones include an appliquéd cotton flag and a two bronze canons marked as taken from Sulu in 1851.The model ships and scaled reconstruction of the port of Cavite is very detailed. There are also several Philippine earthenware oil lamps and palayok from Batangas dating from the 1600's.

The Museo de Americas has approximately 500 objects from the Philippines, many of them dating to the Malaspina Expedition. In 1792, Malaspina and his crew sailed from Mexico across the Pacific Ocean, stopped briefly in Guam, and arrived in the Philippines. The expeditionists spent several months collecting material and botanical samples mostly around Manila.

At the Museo, there is a good number of bladed weapons (with very interesting inscriptions) and an assortment of exquisitely made headgear. The displays however do not have very good labels and some of the materials are either stacked randomly or else shown way up beyond one's line of vision. (the MPMC is still in the process of adding the items into the virtual database).

Still, it is worth the time to wander around at the Museo de Americas, especially when the cultural confluences from within and around the Spanish Lake become obvious to the beholder.

The Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas has 59 objects in its Philippine collection, but none or on permanent display. Alberto Vela, in Tracing Philippine Objects in Unlikely Places identifies some viewable objects at the Cerralbo Museum, a small State-owned museum which houses the art and historical object collections of Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa, Marquis of Cerralbo and the Lázaro Galdiano Museum which houses the art collection of the financier and art collector José Lázaro Galdiano.

****

Not too Invisible

Despite the general sentiment of Spanish neglect of their former colony, raw statistics seem to indicate a different picture - especially in relation to the visibility of Philippine material culture in Madrid. Aside from the permanent displays, the city seems to give a good amount of its institutional spaces to temporary exhibits focused solely on the Philippines. In the year 2021-22 alone, while Kidlat Tahimik exhibited a grand and witty reconstruction of the 1887 Philippine Exposition at the Palacio Cristal, the Anthropology Museum also showed the work of two Philippine photographers, Xyza Cruz Bacani and Geloy Concepcion, in an exhibit entitled Pilipinas ngayon.Filipinas ahora. Later in the year, the Prado will exhibit the work of Fernando Zóbel in a show entitled The Future of the Past. (11/15/2022 - 3/5/2023).

Notes:

(1) There were, of course, some qualifiers in the exuberant praise. The same review chastises Luna for not being historically accurate, and in a paternal tone prefaces the exclamation with "Pero se puede afirmar, sin vacilación de ningún género, que el autor de Cleopatra, si estudia mejor la composición y cuida más del dibujo, es una esperanza legitima para el arte español contemporáneo." 22 June 1881 p. 406

(2)Ocampo, Ambeth R. (Chairman, National Historical Institute of the Philippines) "The Death of Cleopatra" by Juan Luna, from the article "Las Damas Romanas (Roman Maidens) by Juan Luna (The Philippines 1857–1899)", Christie's, Department Information, Southeast Asian Modern and Contemporary Art, christies.com

(3) From the Inventory record of the museum: T-513. Autor Dn Juan Luna. un cuadro que representa Cleopatra. Alto 2.50 ancho 3,40 mts. [nota al margen=] Adquirido en 5000 pesetas; Procedente de la Expopsicion de Bellas Artes de 1881 Rl. O. de 30 de Junio 1881. [con otra grafía=] Pasó al Museo de A. M. See also Sánchez Gómez, Luis Ángel, “Indigenous Art in the Philippine Exposition of 1887: Arguments for an ideological and racial battle in a colonial context”, in Journal of the History of Collections 14, no. 2 (2002), pp. 283 – 294.

(4) Sánchez Gómez, Luis Ángel, “Indigenous Art in the Philippine Exposition of 1887: Arguments for an ideological and racial battle in a colonial context”, in Journal of the History of Collections 14, no. 2 (2002), pp. 283 – 294.

(5)Pulido, Natividad (July 6, 2021). "El Prado 'desempolva' su colección del XIX: más social, más internacional y con más mujeres" [The Prado "dusts off" its 19th-century collection: more social, more international and with more women]. ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved May 3, 2022.