The raw, in time

Exhibit Description

Naif. But in any case sad — less because of the story-as-sculpture intent of its maker. A deeper sadness pervades this thing that at first glance looks like a child carrying another dead child, in a coffin held up like today’s grocery carton. Only, the carrier is a man, not a child, misbegotten by a carver of inadequate skills.

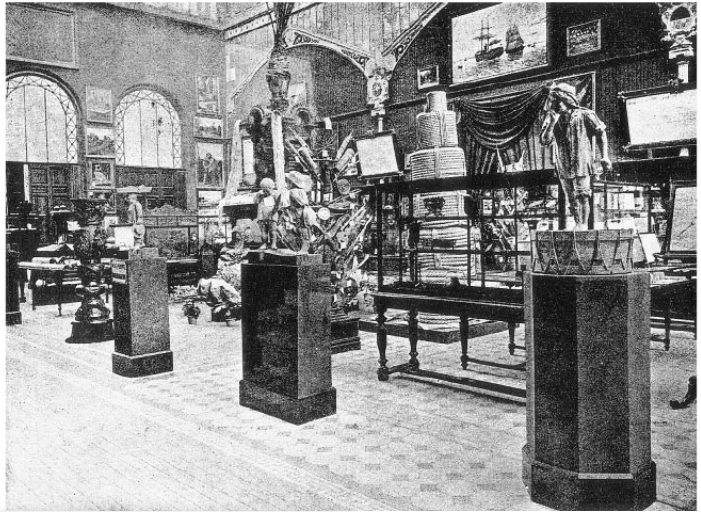

The sculpture was exhibited in the gallery for art at the Exposición de filipinas held in Madrid in 1887. It was staged by an Empire on its last legs. The entire exposition was about a Philippines that was only 11 years from declaring itself a Republic following a war for independence; at precisely a time, therefore, when Spain could use a spectacle of empire and a stimulus for economic growth. An immense undertaking by Spain’s Ministerio de Ultramar, the multi-gallery display, presenting everything from the accoutrements of erstwhile salvajes, to an archipelago of hats, to scale models, to maquettes of Philippine scenes materializing the touristic eye, to minerals and woods, to weapons; the gamut of materiality including actual human beings.

The allegorical figure called “El arraigo de las costumbres” (“The rooting/rootedness of customs”) by its maker, Ciriaco Gaudínez y Javier, was among numerous carvings presented at the exposition, of similarly indifferent value (then and now), together with paintings ranging from mediocre to competent to extraordinary. Recall that the intriguing “The Death of Cleopatra”, with two more paintings by Juan Luna were among these paintings. Already famous for having been awarded gold for “Spolarium” at the 1884 National Fine Arts Exposition, Luna was joined in this exposition by another recognized painter from the Philippines, Felix Resurrección Hidalgo y Padilla.

Writers of the time deemed the sculptures and many of the paintings unremarkable. The stand-out Hidalgo and Luna contributions did not flip two ideas: the Spanish colonial notion of the Philippine indio as possessed of a racially determined incapacity for art; and the ilustrado notion that this incapacity is an outcome of colonial suppression of native potential. The corollary of the latter —that given nurturant education, the indio can realize potential — was upheld by the expatriate intellectuals from the Philippines who thought themselves the embodiment of precisely the persuasive outcome of Western education.

The sadness which appears today to emanate from the man/boy bearing the coffin, apparently of his dead son, may then be imagined as produced by an unhappy ghost of that racism-charged debate.

On the other hand, the sculptors in this 1887 exposition worked in conversation with a Christian moral order. Most of the sculptures, notably including Gaudinez’s “El arraigo...”, were made by residents of the town Paete, province of Laguna, the Tagalog-speaking region to which belongs the Philippines’ colonial capital, Manila. Paete and Manila enjoyed ease of communication, presumably for centuries if not millenia, via the boats plying the largest lake in the Philippine archipelago, the Lake of Bae or Bai (The Lake of the Woman).

A particularly Catholicism-suffused traffic tied Manila’s Intramuros churches and raw artistic talent across the lake, notably, in the towns of Pakil, Pangil, Paete. Among other matters that deserve interest, parents from these towns would bring their young sons to Intramuros to become tiples, or choir boys, at the Manila Cathedral. A wood-carving center producing church statuary and altar adornments evolved in Paete. Pakil was to produce a late 19th century major composer, Marcelo Adonai. And so forth.

In the late 19th century Philippines, while sundry firebrands would debate reform or revolution, and act on their life-or-death decisions, art was only beginning to secularize. For most part, art for the glory of the Catholic triune God and to buttress its moral order was not to release itself into modernity until early 20th century. Luna and Hidalgo left the colony and broke the order of things for themselves: their work should be seen as an early iconoclasm among other iconoclasms needed to create a secular modern state. In the exposition was a momentary juxtaposition of their academically turbo-propped art with the Paete’s collective oeuvre, enveloped in morality tales.

Scholar Luis Ángel Sánchez Gómez1 writes of a “biting and accurate” satirical review of the exposition in “La Avispa” (“The Wasp”, apropos its weekly dose of satire), which nevertheless “never resorts to racial contempt.” Still, notwithstanding its non-racialized critique, the Avispa author dismisses “El arraigo...” thus: “[Gaudínez] does not distinguish between potatoes and the dead”. In general, the reception in Madrid to the art part of the Philippine exposition was witheringly negative.

Another article that Sánchez Gómez cites as having given “a somewhat more complex argument”, was written by Manuel Creus Esther who evaluated “Filipino art” in general in 1888, the year of the Barcelona edition of the Philippine Exposition. Sánchez Gómez notes the long-standing friendship between Creus and Victor Balaguer, the Ministro de Ultramar whose initiative and push had, in fact, made possible these expositions. Wrote the relatively liberal Creus: ‘This is, in short, what we can call Filipino art; an art that represents one of the best achievements of the Spanish colonial task: the assimilation of the native, not the annihilation of the savage.’ ” The conclusion, to Sánchez Gómez, writes somewhat off-key with early statements in the same essay, where Creus says that “ ‘really indigenous Filipino’ painting is merely decorative and ‘rudimentary’ and that ‘it lacked good taste.’ ”

Confronted by the figure, the agonistic face is, indeed, that of a man. The body on the other hand remains as boxy as the coffin (a tree is much more evocative); stereotypical (another tipos del pais variant); and immobile (petrified, in fact). Body is different from head and face. Body is just a plinth for a round head into which the carver’s effort was invested, and who thus created a simulation of outsized grief.

There are many reasons for assigning this and the other Exposition wood figures under the rubric of craft; and its makers, as carvers or artisans, and not sculptors. Some of the reasons are enduring; some are shot through with prejudice. Some reasons matter to art people; some are offensive to nationalists; some are intriguing to political analysts. But it is precisely for these multiple, contradictory responses that Gaudínez’ work, and those of the others, such as Isabelo Tampico, sent to Madrid and Barcelona to flesh out a state-of-a-remaining-colony pageant, compel more than passing interest.

Today, it is possible to take the naif, take apart the concept, reconstruct it and its multiple possibilities, to recognize its material ideas —not as anthropological artifacts, nor craft — but precisely as the arraigo, the “rooting”, of conflict resolution. The present is a dreadful historical moment, but it is a good period for allowing these thoughts to be thought. The awkwardness and indeed weirdness of Gaudínez’ title does, at present, call attention artmaking’s courage on unstable ground.

In any case, a century removed from this exposition, upon which the Philippines’ expatriate intellectuals in Madrid, Barcelona, and Paris cast a collective baleful eye, it possible to escape the awkwardness of the Madrid ilustrados as they tried to think this exposition. In celebrating the genius of Luna and Hidalgo, they were faced with the obvious need to be critical of untutored but cryingly aspirational works in the same gallery of art.

Sánchez Gómez summarizes Graciano Lopez Jaena’s resolution to the quandary, in propaganist’s piece on the Barcelona edition (1888) of this same exposition. It is useful to quote Sánchez Gómez’s exegesis at some length.

Jaena’s brilliant argument no longer holds. The “limitations” of Filipino artists yearning for facility in European artistic languages no longer needs explaning nor excusing. “El arraigo...” can be what it is: simultaneously a naif and a moment of raw fusion of sorrow and aspiration. It may be immaterial if it is art or not. It speaks to today’s Filipino in ways more complex than Jaena would have thought.

Endnotes

1 Sánchez Gómez, Luis Ángel, “Indigenous Art in the Philippine Exposition of 1887: Arguments for an ideological and racial battle in a colonial context”, in Journal of the History of Collections 14, no. 2 (2002), pp. 283 – 294.

The sculpture was exhibited in the gallery for art at the Exposición de filipinas held in Madrid in 1887. It was staged by an Empire on its last legs. The entire exposition was about a Philippines that was only 11 years from declaring itself a Republic following a war for independence; at precisely a time, therefore, when Spain could use a spectacle of empire and a stimulus for economic growth. An immense undertaking by Spain’s Ministerio de Ultramar, the multi-gallery display, presenting everything from the accoutrements of erstwhile salvajes, to an archipelago of hats, to scale models, to maquettes of Philippine scenes materializing the touristic eye, to minerals and woods, to weapons; the gamut of materiality including actual human beings.

The allegorical figure called “El arraigo de las costumbres” (“The rooting/rootedness of customs”) by its maker, Ciriaco Gaudínez y Javier, was among numerous carvings presented at the exposition, of similarly indifferent value (then and now), together with paintings ranging from mediocre to competent to extraordinary. Recall that the intriguing “The Death of Cleopatra”, with two more paintings by Juan Luna were among these paintings. Already famous for having been awarded gold for “Spolarium” at the 1884 National Fine Arts Exposition, Luna was joined in this exposition by another recognized painter from the Philippines, Felix Resurrección Hidalgo y Padilla.

Writers of the time deemed the sculptures and many of the paintings unremarkable. The stand-out Hidalgo and Luna contributions did not flip two ideas: the Spanish colonial notion of the Philippine indio as possessed of a racially determined incapacity for art; and the ilustrado notion that this incapacity is an outcome of colonial suppression of native potential. The corollary of the latter —that given nurturant education, the indio can realize potential — was upheld by the expatriate intellectuals from the Philippines who thought themselves the embodiment of precisely the persuasive outcome of Western education.

The sadness which appears today to emanate from the man/boy bearing the coffin, apparently of his dead son, may then be imagined as produced by an unhappy ghost of that racism-charged debate.

Charged context

Hidalgo’s “La barca de Aqueronte”, one of two of his paintings in this exposition, and Luna’s Cleopatra tableau summon up the passion for allegory that persisted through to the late 19th century in the Euro- American world. From the titles alone of these works by these academically trained, intellectually ambitious artists —self-ascribed like their friends as indios bravos —these were canonical references deployed in Western education. Working in conversation with themes from Classical Civilization, Luna and Hidalgo endeavored a doubling: conveying deft use of allegory to reflect on the state of things in their homeland, and conveying clear evidence of their own erudition.On the other hand, the sculptors in this 1887 exposition worked in conversation with a Christian moral order. Most of the sculptures, notably including Gaudinez’s “El arraigo...”, were made by residents of the town Paete, province of Laguna, the Tagalog-speaking region to which belongs the Philippines’ colonial capital, Manila. Paete and Manila enjoyed ease of communication, presumably for centuries if not millenia, via the boats plying the largest lake in the Philippine archipelago, the Lake of Bae or Bai (The Lake of the Woman).

A particularly Catholicism-suffused traffic tied Manila’s Intramuros churches and raw artistic talent across the lake, notably, in the towns of Pakil, Pangil, Paete. Among other matters that deserve interest, parents from these towns would bring their young sons to Intramuros to become tiples, or choir boys, at the Manila Cathedral. A wood-carving center producing church statuary and altar adornments evolved in Paete. Pakil was to produce a late 19th century major composer, Marcelo Adonai. And so forth.

In the late 19th century Philippines, while sundry firebrands would debate reform or revolution, and act on their life-or-death decisions, art was only beginning to secularize. For most part, art for the glory of the Catholic triune God and to buttress its moral order was not to release itself into modernity until early 20th century. Luna and Hidalgo left the colony and broke the order of things for themselves: their work should be seen as an early iconoclasm among other iconoclasms needed to create a secular modern state. In the exposition was a momentary juxtaposition of their academically turbo-propped art with the Paete’s collective oeuvre, enveloped in morality tales.

Scholar Luis Ángel Sánchez Gómez1 writes of a “biting and accurate” satirical review of the exposition in “La Avispa” (“The Wasp”, apropos its weekly dose of satire), which nevertheless “never resorts to racial contempt.” Still, notwithstanding its non-racialized critique, the Avispa author dismisses “El arraigo...” thus: “[Gaudínez] does not distinguish between potatoes and the dead”. In general, the reception in Madrid to the art part of the Philippine exposition was witheringly negative.

Another article that Sánchez Gómez cites as having given “a somewhat more complex argument”, was written by Manuel Creus Esther who evaluated “Filipino art” in general in 1888, the year of the Barcelona edition of the Philippine Exposition. Sánchez Gómez notes the long-standing friendship between Creus and Victor Balaguer, the Ministro de Ultramar whose initiative and push had, in fact, made possible these expositions. Wrote the relatively liberal Creus: ‘This is, in short, what we can call Filipino art; an art that represents one of the best achievements of the Spanish colonial task: the assimilation of the native, not the annihilation of the savage.’ ” The conclusion, to Sánchez Gómez, writes somewhat off-key with early statements in the same essay, where Creus says that “ ‘really indigenous Filipino’ painting is merely decorative and ‘rudimentary’ and that ‘it lacked good taste.’ ”

Rooting, rootedness

“The rooting of customs” will sound slightly mangled to the 21st century ear for language in either English or Spanish. The dis-ease with the formulation rises faintly from a clearer sense today of the difficulties of fitting personal sorrow to a moral infrastructure so vast and so colonialism-invested as Catholicism. Or, the reverse could have been equally true: a sorrow so vast and supra-personal, into which Catholicism can only be absorbed through the sieve of “customs”. Both could very well have played into the dynamic of carving.Confronted by the figure, the agonistic face is, indeed, that of a man. The body on the other hand remains as boxy as the coffin (a tree is much more evocative); stereotypical (another tipos del pais variant); and immobile (petrified, in fact). Body is different from head and face. Body is just a plinth for a round head into which the carver’s effort was invested, and who thus created a simulation of outsized grief.

There are many reasons for assigning this and the other Exposition wood figures under the rubric of craft; and its makers, as carvers or artisans, and not sculptors. Some of the reasons are enduring; some are shot through with prejudice. Some reasons matter to art people; some are offensive to nationalists; some are intriguing to political analysts. But it is precisely for these multiple, contradictory responses that Gaudínez’ work, and those of the others, such as Isabelo Tampico, sent to Madrid and Barcelona to flesh out a state-of-a-remaining-colony pageant, compel more than passing interest.

Today, it is possible to take the naif, take apart the concept, reconstruct it and its multiple possibilities, to recognize its material ideas —not as anthropological artifacts, nor craft — but precisely as the arraigo, the “rooting”, of conflict resolution. The present is a dreadful historical moment, but it is a good period for allowing these thoughts to be thought. The awkwardness and indeed weirdness of Gaudínez’ title does, at present, call attention artmaking’s courage on unstable ground.

In any case, a century removed from this exposition, upon which the Philippines’ expatriate intellectuals in Madrid, Barcelona, and Paris cast a collective baleful eye, it possible to escape the awkwardness of the Madrid ilustrados as they tried to think this exposition. In celebrating the genius of Luna and Hidalgo, they were faced with the obvious need to be critical of untutored but cryingly aspirational works in the same gallery of art.

Sánchez Gómez summarizes Graciano Lopez Jaena’s resolution to the quandary, in propaganist’s piece on the Barcelona edition (1888) of this same exposition. It is useful to quote Sánchez Gómez’s exegesis at some length.

“Jaena was able to contradict the opinions of friars, conservatives and even most Spanish liberals on the backwardness of the Filipino natives. The Filipino writer understood his compatriots limitations, their not very advanced techniques and their rudimentary expression of form, but he turns the argument on its head and takes these points, citing their works of art, however simple or prudish, as samples or unconscious reflexes of the repressed social conditions in which Filipinos lived and in which they could see their incipient artistic abilities and capacities wasting away.”

Jaena’s brilliant argument no longer holds. The “limitations” of Filipino artists yearning for facility in European artistic languages no longer needs explaning nor excusing. “El arraigo...” can be what it is: simultaneously a naif and a moment of raw fusion of sorrow and aspiration. It may be immaterial if it is art or not. It speaks to today’s Filipino in ways more complex than Jaena would have thought.

Endnotes

1 Sánchez Gómez, Luis Ángel, “Indigenous Art in the Philippine Exposition of 1887: Arguments for an ideological and racial battle in a colonial context”, in Journal of the History of Collections 14, no. 2 (2002), pp. 283 – 294.

Explore items in Exhibit

El arraigo de las costumbres

Translated as The Rootedness of Customs or the Rooting of Customs, this is a wooden sculpture of a man carrying a small open coffin with the lifeless body of a young child.

La muerte de Cleopatra

In Cleopatra, Luna dramatises the death of the Egyptian queen, a longstanding and popular subject in European painting. As penned by the Greek biographer Plutarch, Cleopatra was discovered dead in her chamber by Augustus Caesar´s men, dressed in her…