Costumes, colleciónes del trajes, costumbres, costumbrista

Exhibit Description

The taxonomic eye Part 2

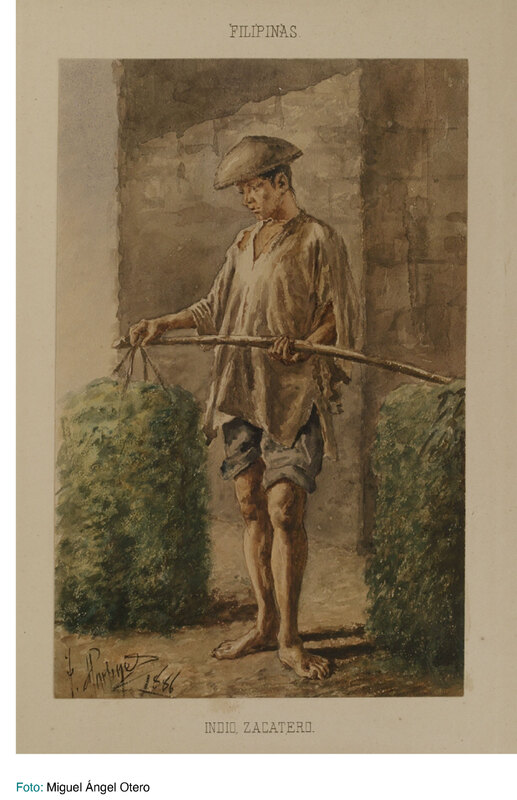

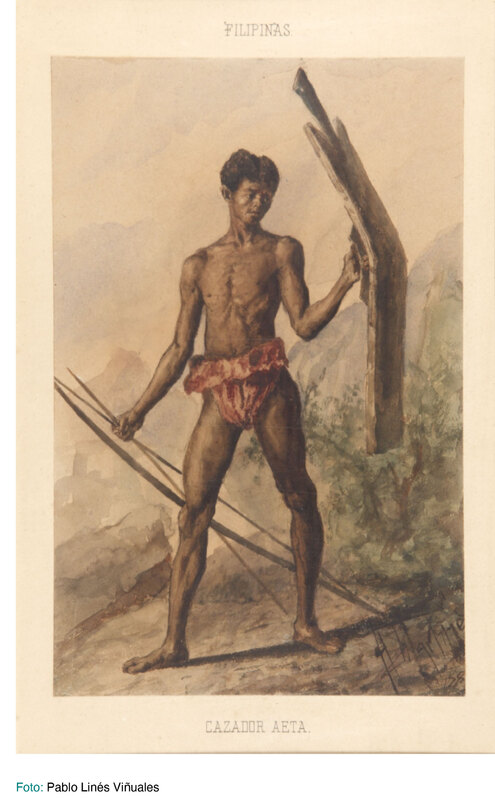

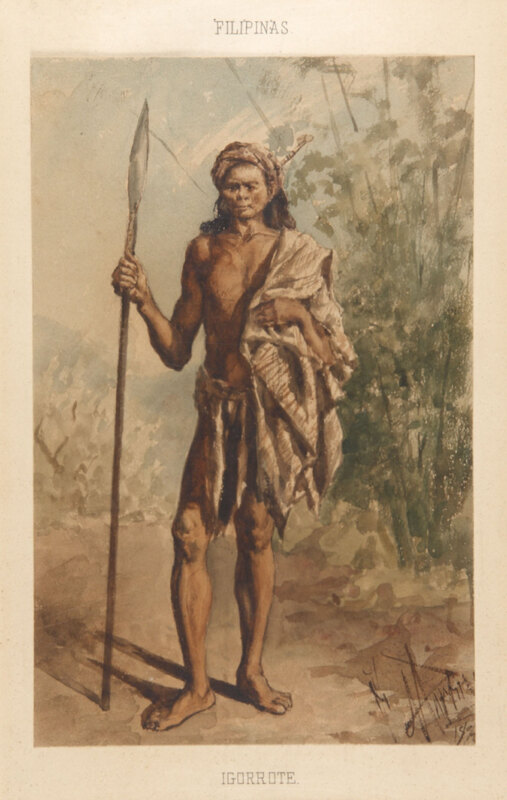

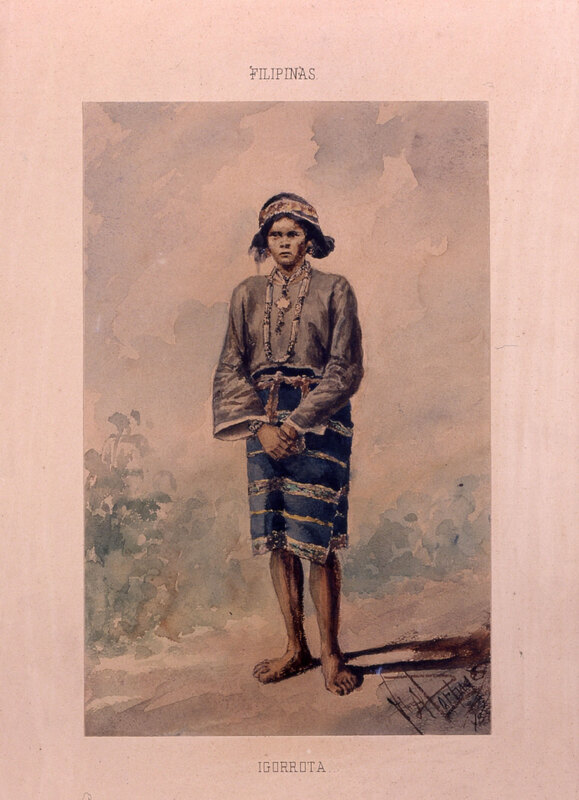

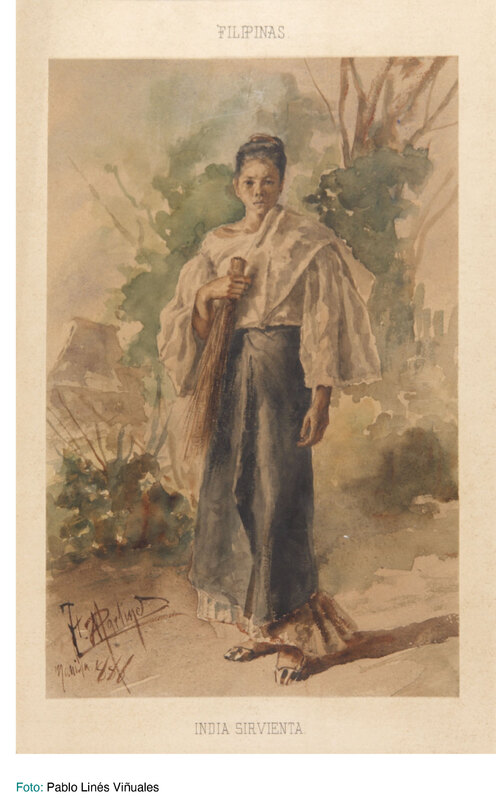

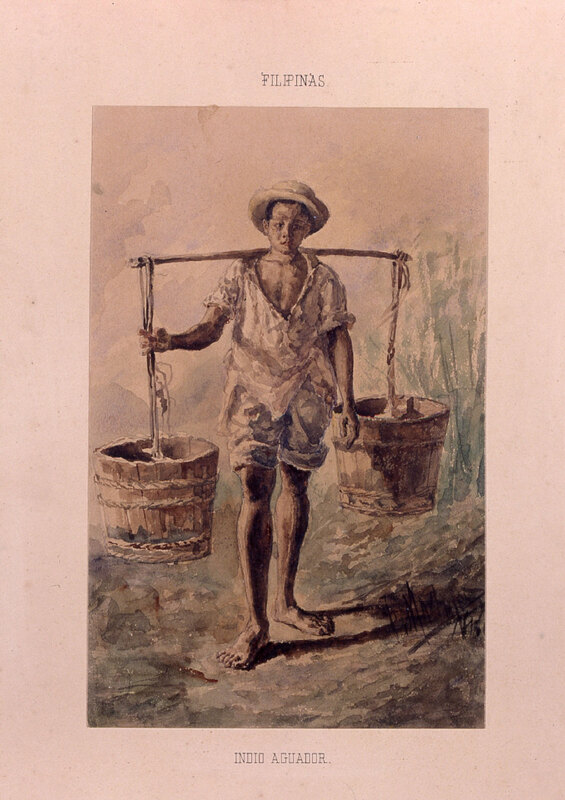

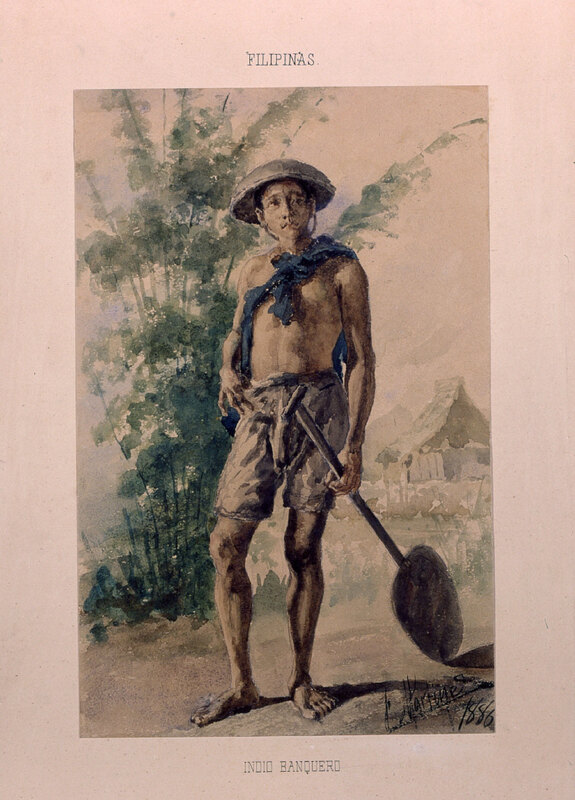

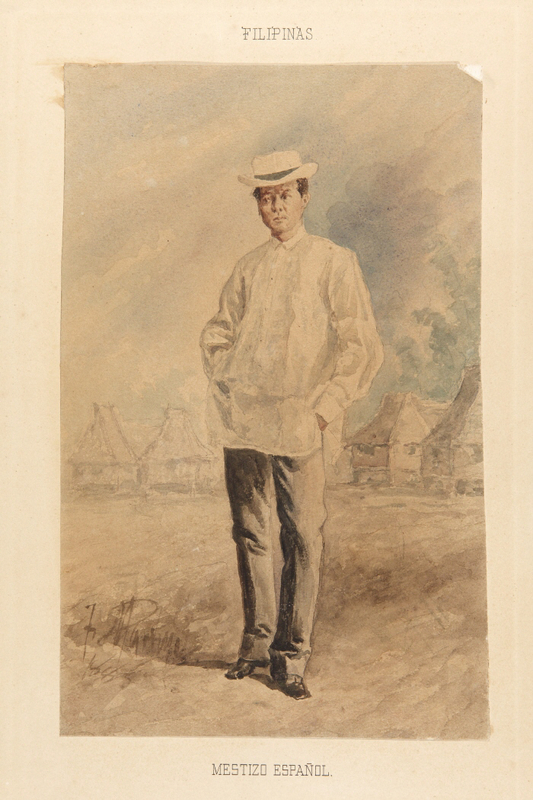

In the Philippines, where the tipos del país of previous centuries are collector prizes, the watercolors invigorate nationalism. One painting that clearly belongs to the set in this exhibit fetched upwards to nearly half a million pesos in a recent auction. Most of the set, however, has belonged to the collection of the Madrid’s Museo Nacional de Antropología since 1887. It comprises 18 watercolors. It is uncertain how many watercolors in all were painted by the Manila artist Félix Martínez y Lorenzo in 1886 to complete the set, but his name is certainly not unknown to the Philippine culturatti.On the lips of connoisseurs are the sources of delectation. The words—“Filipino”, “mestizo”, “India mestiza de China”, “Mujer Tagala”, and so forth—seem to the citizen Filipino today to be delicious affirmation of a single version of a nation’s narrative of becoming. Collectively, the tipos del país are among the subtlest and most insidious of the drivers of a vision of the Philipines as a collection of “races” and classes. That this vision is cultivated by those who perceive themselves atop the social pyramid has driven collecting and sustained enthusiasm.

This vintage 20th century retroactive formulation of what is Filipino, fed by fragments of the 19th and earlier centuries, remains sealed off by that enthusiasm from critical examination. Yet it is critical examination that discloses the greater value of these artifacts of cultures that gaze at and pin up, so to speak, human specimens. Those cultures, plural, overlap across myriad geographies.

Costumbrismo

The Augustinian priest and scholar Blas Sierra de la Calle (1) accurately described Martínez as a landscape painter, portraitist, and pintor costumbrista. The English rendering of his essay translates costumbrista as “genre views”. It is accurate enough but inadequately conveys the cultural inflection of the Spanish original: a word that gathers costumbre, “custom” and manners (the French mœurs), but moreover the social interest itself in the variety of lifeways within a politically defined realm. The English “genre” is inflected to be close to generic; hence anaemic instead of colored by specificity.This parsing allows exploration of the long shadow—invisible for most part in the Philippines—behind the term tipos del país. The tipos-form belongs to the larger history of costumbrismo in Spain. And this Spanish literary and painterly attention to the folkloristic and the mundane is in turn part of a European and Latin American fascination, in the 18th to the early 19th centuries, for what came to be called ethnicities in the 20th. A Spanish historian called it an anthropological perspective of history. (2) Costumbrismo for Spain was counterpoint to the heroic exuberance of the Baroque, happening at the same time. This perspective produced by a collective fascination was seemingly inward looking:

“This movement, which flourished in the 19th century, sought to explore the nature of the Spanish character by investigating the lived experience of contemporary Spaniards. Its significance lies in its agnosticism with respect to any divinely ordained mission for Spain and in the fact that it brought to the fore so many of the lasting themes and motifs of subsequent discussion of Spanish distinctiveness.”

Emerging in other parts of Europe for different reasons —notably in Germany where the Spanish indígenas was the indigene völker, and the pueblos indígenas were the einheimische bevölkerungsgruppen — the eye on the ordinary quickly shifted to ruinous ideology. The German Völkisch movement descended into outright anti-Semitism and other racisms; eventually to the Nazi social engineering. In Spain, the aristocrats who hardly depicted themselves in these costumbristo images, cultivated an urbanity that collected images of non-urban and colonized types.

It was indeed the Spanish (typically Madrileño) aristocrat’s eye that taxonomized their urban inferiors and the denizens of rural Spain, with emphasis on the exotically clothed. Hence there was a preponderance of painted and photographic tipos del país of al Andaluz, which remained Moro in cultural texture; País Basco, which had always been strange; and in some respects Catalonia. In the costumbrista images and literature, separately or jointly, quaint humans were recorded going about their typical days or posed in clothing that therefore conflated with costumbre; eventually with the English word costume.

José M. de Freixas’ Enciclopedia de tipos vulgares y costumbres de Barcelona ("Encyclopedia of vulgar types and customs of Barcelona", 1844) or Fernán Caballero (pen name of Cecilia Francisca Josefa Böhl de Faber) for example, in the prose portions of her Cuentos y poesías populares andaluzas ("Popular Andalusian stories and poems", collected in 1859) are good examples of the relationship of those looking and classifying, from those looked at and classified. The idea of costume underwrote classification.

Costume

The word costume became inseparable from acts of classification, not only in literature and painting (eventually print), but in exhibitions. Some of the most popular attractions at the universal expositions everywhere in the Euro-American world, from their commencement in the mid-1900’s, were scenographically fabricated pueblos summarizing what could be held in the popular imagination as cultural wholes. The scenographic pueblos—simultaneously people, village, town, the people, populace, folk—physically delineated the classification. So, too, did the tipos del país freeze classification. The cards or watercolors were as though mobile exhibits. And so there were pueblos arabes, pueblos mexicano, and so forth, not only signifying types but of typicality in these 2 and 3 dimensional forms.Clothing imagined as typical—that then congealed into types of wear and by extension types of humans—glued the words costumbres and costumes together. From the hindsight of the 21st century, the fusion of clothing and identity was to harden so extremely that typecasting by the clothes one wears is thought to be natural. The Martínez watercolors carry on with more than half a century of the attention to clothing that commenced in the Philippines with Damian Domingo’s early 19th century tipos del país. Martínez’s "Moro de Joló" is an excellent example of the eye for detail of clothing and accoutrements that makes for a visual summary with an anthropological spirit. The watercolor is unlike the painterly renderings of artists of the same period, notably Juan Luna, for whom clothing contributes to but do not overwhelm the sitter’s personality as individual.

Martínez’s Moro is a type rather than an individual. His Joló man is beautifully executed with quick, gestural colorings that pre-date Impressionist ambition by Filipinos. The rest of the set were executed to present the iconographic sameness necessary to establish a taxonomic project. Still, because Martínez was a gifted product of the University of Santo Tomás, his tipos del país in Madrid have qualities suggestive of some attention to individualized humanness: the body postures that suggest personal attitude, the facial assertiveness of each person painted, and arrested moments of individualized body movement. But the costumbrismo within which he worked confined these qualities to an over-all sensibility: enjoying the privilege of consuming the peoples of the world through images.

Martínez’s cuadros de costumbres (scenes of customs or sketch of local customs) is only one type of costumbrismo. The artistic world to which he connected himself—from the Philippines, since he was not educated in Europe—elsewhere strengthened a way of seeing that, among others, profoundly impacted Latin American literature; that was enlivened early but forthwith transcended by such artists as Goya, who would find intellectual, political, and aesthetic projects without this taxonomic eye; and that was part of a huge turn to the European folk/völk as Modernism picked up momentum. As the main illustrator for La Ilustracion Filipina (1893-1895), Martínez lived in the flow of ideas from the Euro-American world; but was not part of a critical cutting edge.

His tipos del país and indeed his other extant paintings exhibit his abilities to extend if not slightly escape the form. Particularly in giving less centrality to costume and greater attention to individuation, Martínez shows a man of his time and place—he was familiar with the wealthy districts of Manila—who can also be quite a product of his own talent. That is to say, his talent did not confine him entirely to the exoticizing trajectory of the genre he worked within. If only for this reason, Martínez deserves greater attention.

Fashion and nation

The slippage from costumbrismo into such curious cultural forms as that titled in a Google page as Tipos Del Pais (Philippine Fashion Plates), or Disneyland’s “It’s a Small World, After All” experience, should unearth such obscure ideas contained in the early 18th century French word, in turn from Italian, custume “custom, fashion, habit”—ultimately from the Latin consuetudo. This a rather old lexical taproot.Today, the notion of “national costume” should at least be seen as essentially owing to costumbrismo. This affectation may be described as a self-ethnographizing, and posturing as a wo/man of the earth of the país. In this manner, the wearer performs the nation. The wearer as also the collector of tipos del país made by Filipinos, are not known to pay too much attention to the racialized social classifications that this idea of performing the nation preserves. A century ago, the Martínez tipos de país arrived in Madrid to be exhibited at Madrid’s 1887 Exposición Universál, less than a decade before a war of national liberation won sovereignty for the Philippines from Spanish colonial rule in 1898. It may not be mere provocation to suggest that Martínez may have had a sharper understanding of confinements imposed by his milieu than today’s performers of nation.

Notes:

(1) Blas SIERRA DE LA CALLE, Félix Martínez y Lorenzo en La Ilustración Filipina. (Cuadernos del Museo Oriental-Valladolid, 14). Museo Oriental, Valladolid 2015, viii-148 pp. (62 ilustraciones), 24 x 17 cm.

(2 ) Maravall, José Antonio, Culture of the Baroque: Analysis of a Historical Structure”. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1986, p. xvi.

Explore items in Exhibit

Moro de Joló

Plate representing a Muslim man from the southern Philippines ( Jolo in the Sulu Archipelago)

Signature at the Lower Right Corner: Martínez y Lorenzo, Félix

Félix Martínez

Mora de Joló

Plate representing a Muslim woman from the southern Philippines. (from the Sulu Archipelago)

Signature at Bottom left: Martínez yLorenzo, Félix (1886)

F. Martinez