Provocative Beauty

Exhibit Description

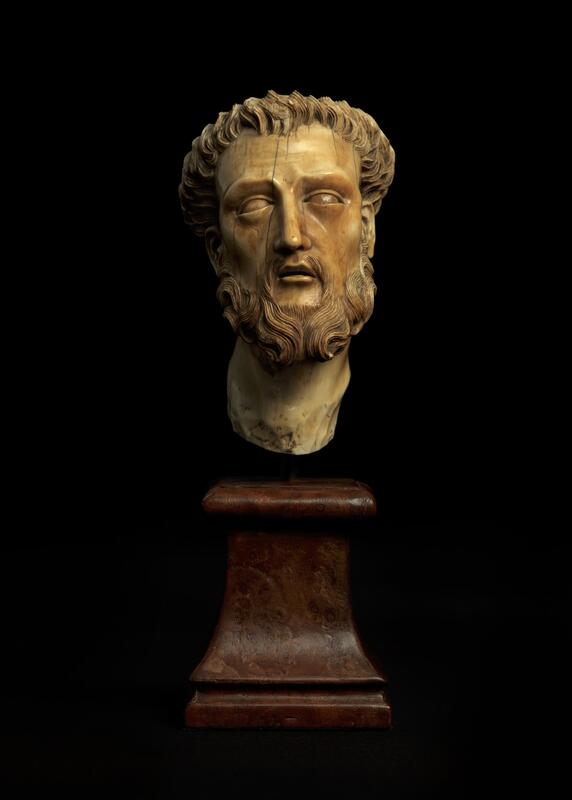

Francis Xavier had only been deceased 78 years, and had only been canonized as Saint for 18 years, when this bust was created in Manila in 1630. The realistic assumption is that an individual relocated to Binondo from the fringes of the Middle Kingdom —individuals currently called Chinese—sculpted it.

The ivory figure was recently gifted to the British Museum by a couple, patrons of the august institution, which classifies it under its Philippine Collection. An extended annotation describes it as “Hispano-Philippine sculpture” of ivory; “a masterpiece of individualized portraiture”.

The annotation by Dora Thornton for the British Museum Magazine in 2018 added that it “must be counted among the very best of Hispano-Philippine ivories to have survived”.

The British Museum taxonomy thus figures the Philippines as a place. Among other facets of this spatial definition is the impulse to emplace a culture that connoisseurship circles call Hispano-Philippine. It reckons the erstwhile las islas filipinas as a pivotal node in a maritime traffic involving the many entrepots of China, Mexico, island and peninsular Southeast Asia, and South Asia.

By the first half of the 17th century, Manila was already the fulcrum of what is today grandly intoned as the Galleon Trade, the economic order Spain built to traffic in the fruits of empire. The trade began in 1565 (earlier than the founding of Spanish Manila in 1571), the year the Augustinian priest-navigator Andres de Urdaneta figured out and rode the Kurioshio Current in the northern Pacific, to accomplish the tornaviaje from Manila to Acapulco.

The superb St. Francis Xavier figure is located by the British Museum in a transcultural setting. The likely Binondo place-of-make, across the river from Intramuros, distills the substances from an entire empire. The term “Hispano-Philippine” is indeed widely understood to include the infusions of Chinese talent, proclivities, networks.

The Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade may also be called the China-Americas-Spain Trade, with Manila serving as consolidation center supervised by globalization-minded investors, and as supplier of boat-building and seamanship skills (and, needless, to say, the hardwoods); and with Acapulco well-situated as redistribution center in the direction of South America and the Atlantic.

The ivory St. Francis materialized from out of the virtuoso hands of a transplant from the Asian mainland. He (or she?) lived temporarily or permanently amidst an Intramuros-Binondo population that was well on its way to leaving its 16th century dalliance with Islam, to take up the Roman version of Christianity, its love for a rather animistic pantheon of saints, and the adherents’ wont to venerate or implore sculptural figuration of different divine personalities.

The observations made in the British Museum annotation deserves further elaboration: the eyes are almond shaped; the frontal aspect, a bilateral symmetry (with hair and beard executed rather mirror-like across the sides of the face); the brow is made tense by slight mounding; and the delicate mouth has teeth. The figure is understood to be a response to the increasing need for the material props to evangelization. In the case of this particularly awesome St. Francis, the imitation of a European santo figure of the period clearly surpassed many originals.

And so this figure—which is Philippine if the Philippines is regarded as the once-upon-a-time intersection point of world-changing currents, hothousing the inforescence of genius local responses —does not conveniently align with current nationalisms. This Francis belongs to the intersecting currents themselves. Its relationship to the Philippines as lived experience by the colonized indio is not via its making, but —speculating now—through the compelling beauty that was supposed to and indeed did sustain the operations of conversion to Christianity. As even lesser saint-sculptures managed to do.

Such beauty, which originated cross-culturally as Christianity was embodied in ritual object-making by Chinese hands (this object is superbly Eurasian, although it is not Euro-Pacific), became Philippine as the indio proceeded to reshape this monotheism within local knowledge. That re-shaping is an on-going story, and it is anyone’s guess what forms of Christianity are possible, viable, or conceivable in the future for Filipinos.

Meanwhile, today, students of Filipino nationalism should be quite provoked by the evasiveness of this kind of object to any force-fitting to narratives that separate nation from globalization. Births of nation transpired to distinguish one imagined community from others in the world. But the more difficult piece of narrative-making involves the nation as precisely cross-cultural, and impossible to disentangle from global forces.

St. Francis himself was a historical figure set on a globalizing mission. The “Apostle of the Indies” proselytized in the Moluccas, Malacca, Goa, Japan, and Macau. A contemporary of Ignacio de Loyola and witness to the birth of the Society of Jesus with a determined evangelical mission, indeed deploying a military metaphor (e.g. “soldiers of Christ”), St. Francis and the Jesuits opened up virgin apostolic fields in the Americas and the Indies. Epic narratives were to spin restlessly out of these early ventures.

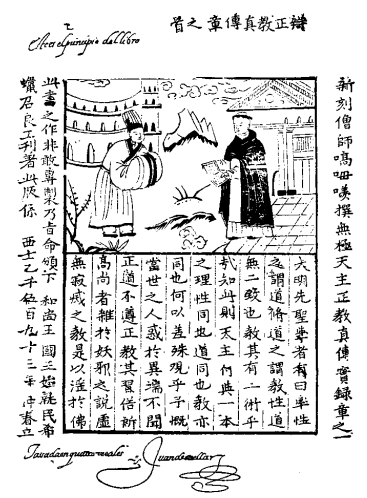

The Jesuits were slightly preceded in the Philippine field of missionary work by the Dominican and Augustinian Orders. The Dominicans in particular thought of the Manila as a launching pad for the true mission: the proselytization of China.

The “Indies” or Greater India did not and does not include the archipelago that would be called las islas filipinas in the 16th century, and the Philippines in the 20th century. It should have been a fairly quick shift for the thousand-year old orientation to the India trade of island Southeast Asia to be eclipsed in the Philippines with the high-octane orientation to China that began and persisted with the galleon trade.

The Philippines’ beloved St. Francis, who in his peripatetic life stitched together the nodes of these Indies and East Asia before the galleon trade began in earnest, materializes in the present through this ivory figure, and with its sheer exquisite presence to challenge simplifications about identity-formation.

The small sculpture in ivory —itself emblematic of violent global traffic — provoke concepts of nation that are equally fierce about sovereign territory as it is embracing of the complexity of relations between inside and outside.

In Dialogue

Archiving reader reactions and comments

An award-winning poet writes a poem based on this object

Surely your iris-less eyes are unable

To imagine us looking at you

In your vitrine case as you float impaled on a post.

See the full poem ...

—Marne Kilates

Facebook March 22,2021

On the involvement of other South East Asian Countries in the galleon trade

...While Chinese silks were much in demand in the Americas, so were Indian cottons in all their diversity - calicoes, muslins, brocades. I found this out in a study I made of the correspondence between merchants in Manila- Mexico and Cadiz in the late 18th century for a Mexican project I was in. Pedro Murillo Velarde lists the amazing diversity of peoples in Manila during the 1730s from Persia, all over India, Southeast Asia, not to mention Europeans of all kinds.

Follow the conversation here...

—Fernando Zialcita

Facebook March 22,2021