British Country Houses and Philippine Prizes

Exhibit Description

In the United Kingdom, one of the repositories of early modern objects originating from Manila may be found, not so much in Museums, but in British country houses. Over the years, the stately homes of the landed gentry have yielded Philippine objects of great academic and historic value. The presence of these objects on British soil is a historical inflection point - a reminder that the Philippines, in the early and late modern period, was a transcultural matrix, a hub on the edge of both worlds for both Intra-Asian and Trans- Pacific Galleon trading, and a crux for inter-imperial jockeying for possession, profit and prestige in South East Asia and the Pacific.

The pathways for how Phiilippine objects were set in place in Britain in this period, vary from the gifting or purchase by English merchants “country trading” via the South China trade network, to individual privateering/piratical ventures like Thomas Cavendish’s in Iloilo in 1589 and Dampier’s of Mindanao in 1686 or the East India Company’s scoping missions carried out by Alexander Dalrymple in Sulu from 1761-64. Then there were the captured Manila Galleons (four in its 250 year history and all by the English), massive Spanish ships loaded with either “Manila” trade goods, Mexican silver, personal properties of retiring Spanish officials or contraband luxury goods.

Of the several thousand British country homes ( a majority of them under the National Trust or the English Heritage Trust), our research has yielded over fifteen that have some South east Asian connections. The more well-known houses would be Shugborough Hall, with George Anson’s “gold dust jars” and pieces of Spanish silver.

Holland House in Kensington, had the Boxer Codex in Lord Holland’s library until 1945. It was auctioned off after the House was destroyed by the war, and eventually purchased by Charles Boxer and donated to the Lilly Library in Indiana.

William Draper’s “Manilla Hall” in Bristol, was supposed to have displayed the Niño Dormido, the sleeping ivory Christ child later purchased by Bangko Sentral in 1981 at an auction at Christie’s. The owner of the lot that sold the Niiño was the Fourth Lord of Leigh. .How the ivory got from Bristol to Stnoneleigh Abbey in Warwickshire is anyone's guess, but there did seem to be an orientalist trend in the later early modern period that was fuelling the collecting proclivities of the wealthy owners of these estates.. Alnwick Castle and Syon Park , both the estates of the Duke of Northumberland, auctioned off a Pedro Velarde Map at Sotheby’s in 2014.

Then there is Melford Hall - its Philippine objects probably the most directly provenanced to a single historical event.

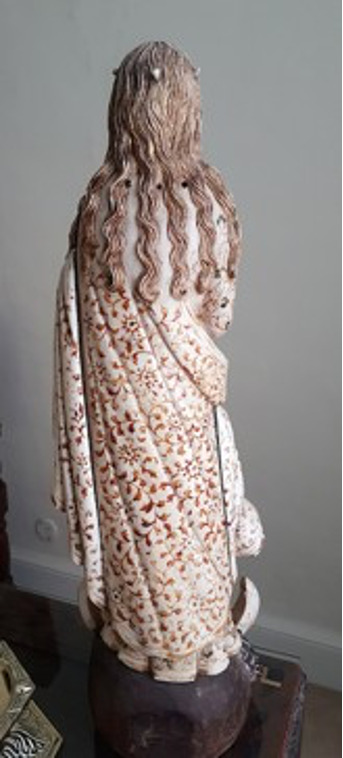

Sir William Hyde Parker’s family biography published in 1867 attributes several items at Melford as taken from the Spanish galleon Santissima Trinidad, which his great grandfather, Admiral Sir Hyde Parker, 5th Bt (1714–1782), captured off Manila in 1762. The items he attributes to the ship consists of pieces of porcelain, two Qing jars meant to be gifts to the Spanish King from the Emperor of China, and ivories - the biggest of which were a Madonna and a Niño.

The Santíssima Trinidad or “El Poderoso” (the slow one), was one of the largest Manila galleons ever built for trading between the Philippines and Acapulco, and when it was captured by the Biritsh,, its hold was filled to over-capacity with an assortment of all kinds of goods. It had crossed the Pacific several times years before, but this time, had turned back to Manila in order to repair damage from a storm. The British, eager to capture the Saint Philippina for a naval prize in Mexican silver, mistook the Trinidad with all its outbound Asian cargo and now were stuck with trying to exchange the cargo for currency.

An inventory of its official cargo, preserved in the Hyde-Parker archives, listed thousands of bundles of silk cloth, 85,000 pairs of socks, boxes of cloths from Bengal, iron pieces, spices, and crates of brocaded silks (12,000 pieces) and a total of 134,610 porcelain pieces (1) Two Spanish merchants, Don Francisco Vizente Meylar and Don Juan Francisco, whose stock had been taken by the English, later petitioned the Admiralty Court for remuneration on the grounds that no inventory of the ships’ content and been taken and that the number and value assigned by the English to the captured goods was way off. Many luxury goods were "undeclared."

A Don Henriquez petitioned the Admiralty Court, later condemning the taking of the Trinidad as illegal, as he sought to get back his personal property. losses. (F49/2,1765) Henriquez complained how “Desks, bundles, and chests were broken open, and many things of great Value .. were .. taken out of them and landed at Cavite.” (IOR,77)

So despite the absence of an explicit mention in the 1765 inventory, the Madonna was in all likelihood on The Santissima Trinidad. Many scholars attribute this common silence to the fact that ivories and jewellery were contraband as cargoes on the Galleon, and were most likely shipped as personal property. The Madonna itself bears common characteristics of HIspano-Filipino ivories. ( both Esperanza Gatbonton and the late Estrella Marcos both confirmed its Philippine provenance after seeing the photos I showed them).

The presence of the Madonna at Melford Hall encourages a lot of questions. Was the Madonna meant to go to the Cathedral in Mexico? Was it commissioned by the Augustinians or was it Henriquez’s private property meant to be donated to a cathedral in Seville where he was meant to retire? Why did the Hyde-Parkers keep the icon?

The story of the Madonna evokes many poignant questions around displaced religious objects, collecting proclivities and the intersections of power, empire and military might. It also allows one to look at the network of British and Spanish inter-imperial wrangling around colonies, religion and the prestige of self-authentication through objects.

REFERENCES:

F49/2(1765) Capture of 'Sanctissima Trinidad': question of whether the prize was governed by agreement made between army and navy re the capture of

Manila. Case and opinion.

F1002/93/12(1764) Mr Read to Harry Parker, from the Grafton at Spithead. Concerns that if the Sanctissima Trinidad goes into Lisbon the Portuguese might seize her. English customs have taken the Indian fabrics and goods Mr Read had been bringing for Capt Parker's wife.

India Office Home Miscellaneous Series, c.1600-c.1900, (I), vol. 77 pp.87-91

(2) Cushner, Nicholas. Documents Illustrating the British COnquest of Manila 1762-1763. London, 1971.