Bagobo Material Culture at the American Museum of Natural History

Exhibit Description

(Shared data for this segment of the AMNH's extensive Philippine collection was given to the Mapping Project via a SOAS IKE grant fund for a Bagobo Tagabawa-Klata Community Knowledge Co-Creation Workshop held in August 2023. Read more about bringing this data back to its source cultures here:) https://philippinestudies.uk/mapping/bagobo-repatriating

Following the colonisation of the Philippines by the United States in 1898, the American Museum of Natural History in New York introduced a Philippine Hall within its recently built West Wing. In 1909, the museum officially opened this exhibition, presenting a diverse assortment of Philippine cultural artefacts. The hall displayed a wide range of items, such as textiles, basketry, brassware, jewellery, weaponry, pottery, as well as life-size reconstructions of native dwellings, life casts, and various exhibits that provided a glimpse into the daily lives of indigenous communities in the Philippines..

The core of the collection was donated by then AMNH president and one of its founders, Morris K. Jessup (1830 - 1908) in 1905. A noted philanthropist and patron of scientific research and the arts, Jessup acquired the majority of his collection of Philippine materials from the 1904 St. Louis World Fair, where the Philippines was prominently displayed. As a way to introduce America's newest colony to the world stage, the Philippine Exposition was a grand showing, comprised of over 70,000 exhibits and 113 buildings spread across 47 acres. Over 1,000 “natives” from the Philippines were brought to Missouri to be part of the “living exhibits,” and were displayed in six reconstructed villages replicating those of the Visayans, Igorots, Moros, Samals, Bagobos and other Philippine “tribes.”

The Philippine Reservation, as it was termed then, was an unprecedented ethnological exhibition and display of the expanding American empire in the Asia-Pacific. While its legacy continues to be debated, it has undoubtedly stirred the curiosity of many Americans to travel and explore the islands in the early 20th century, including anthropologist Laura Watson Benedict (1861 - 1932), who went to Davao in Mindanao to study the Bagobos from October 1906 to December 1907.

Benedict was said to be captivated by the culture of the Bagobos, who were singled out by the St. Louis World Fair organiser Albert Ernest Jenks and then Chief of the Ethnological Survey, for their “barbaric custom of human sacrifice,” and equally for their “developed artistic sense.” (1)

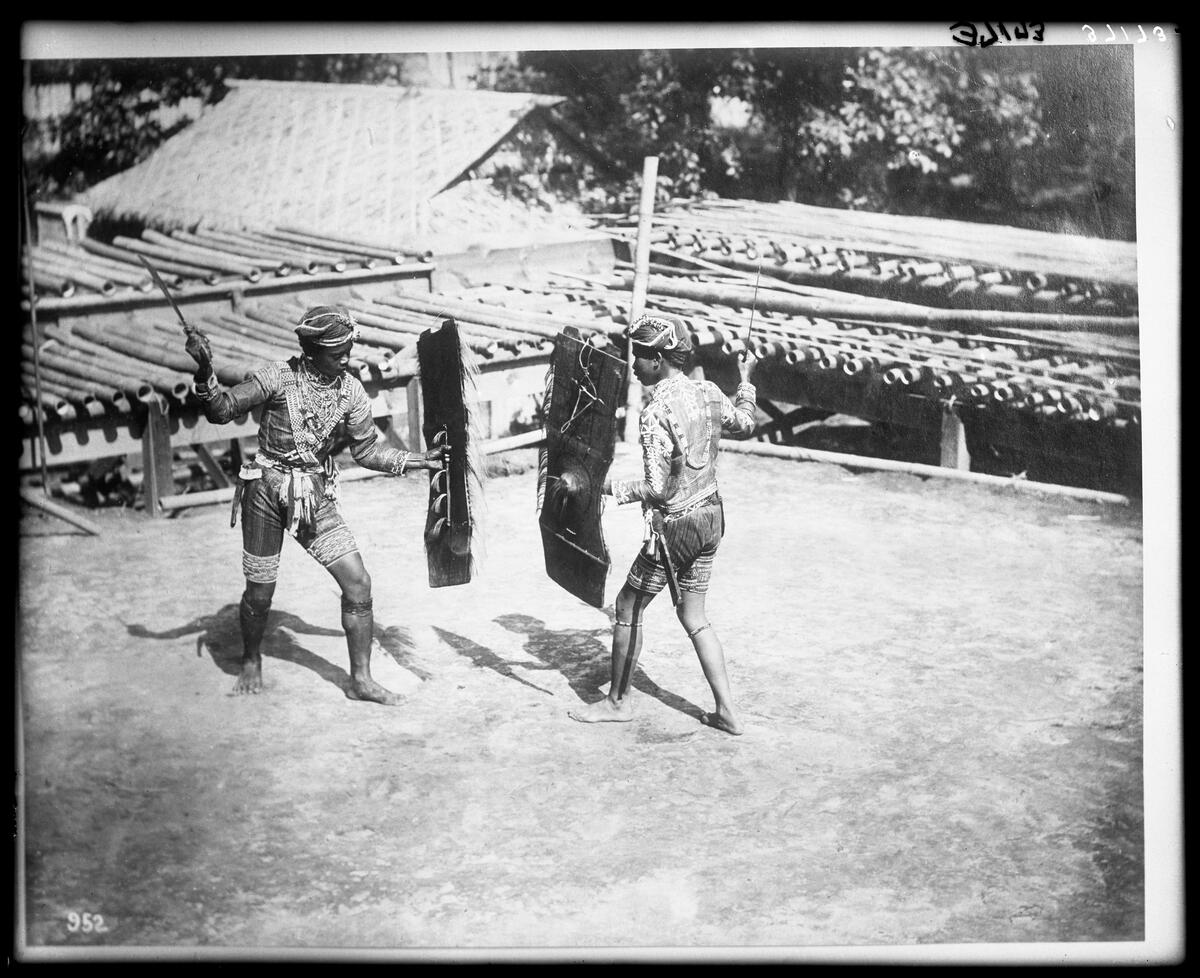

One of the many indigenous peoples groups in Southern Mindanao, the Bagobos were settled around the area of Mt. Apo and the Davao Gulf. They produced fine quality textiles, clothing, weapons, shields, and accessories, which were intricately decorated with colourful beadwork. By the time Benedict arrived in Mindanao, there was already a brisk trade of these items particularly among American military officers and other anthropologists stationed in the area.

Benedict was described as a “passionate collector” and acquired a total of 2,534 Bagobo artefacts during her stay in Davao, including many fine examples of abaca textiles. Upon her return to the US, she initially offered her collection to the Field Museum in Chicago, but they did not meet her asking price. The collection was eventually purchased in 1910 for $4000 by the AMNH, who also hired her to catalogue the collection. She published her research in 1916 under the title Bagobo Ceremonial, Magic and Myth which has since become a foundational text on the subject. Recognised as a “forgotten pioneer” in the field of anthropology, her collection at the AMNH has also been the focus of several subsequent studies.

The third significant contributor of materials to the Philippine collection at AMNH is Frederick Starr (1858 – 1933), curator of the anthropological collection at AMNH and also Benedict’s professor at the University of Chicago. Starr also did fieldwork in the Philippines in 1908, upon the invitation of his former students who held government posts in the Philippines. Both the Benedict and Starr collections were purchased by AMNH using funds provided by Jessup. Additional donations were made in the following years, including the collection of photographs of Dean C. Worcester, who served as member of the Philippine Commission and Secretary of the Interior for the US government in the Philippines from 1899 to 1913.

The Mapping Project's virtual collection features 139 examples of Bagobo material culture at AMNH, which were assembled from the collections of Jessup, Benedict and Starr. The collection includes a variety of objects both for ceremonial and everyday use of the Bagobos. Highlighted in this selection are abaca textiles and clothing; jewelry and accessories; knives and weapons; bags and baskets; bamboo tubes; and brass betel nut boxes.

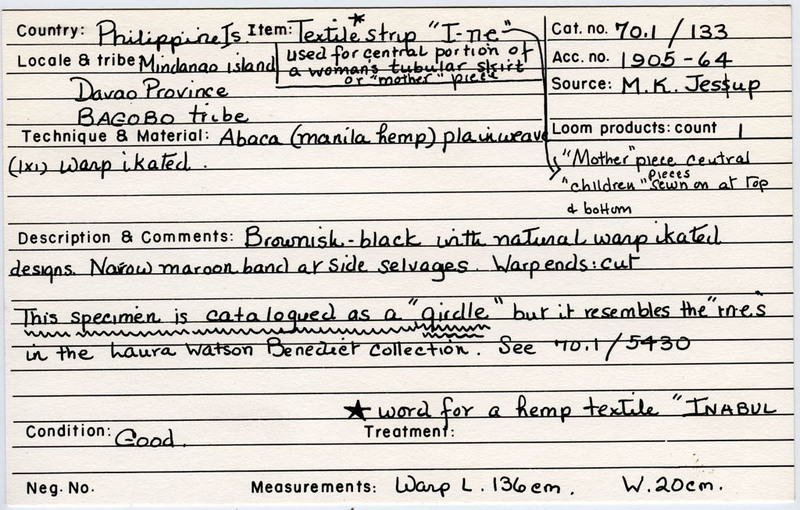

Added to the collection items are some of the field notes by Benedict and cards done by Lisa Whittall, AMNH’s assistant curator of textiles from the 1970s to 90s. The additional documentation helps to identify the materials commonly used by the Bagobos, such as abaca, I-ne, wood, beads, and bells. In addition, they also identify techniques such as plangi (tie-dye technique), tutuc (applique) and ikat.

Abaca textiles and clothing

Abaca or Manila hemp is a knotted plant fibre from the stem of the Musa textilis, a species of banana native to the Philippines. Since the 19th century, it has been widely cultivated as a commercial crop across the country and is traditionally woven by women into cloth and used in bags and other accessories by many indigenous communities, including the Bagobo and the Tboli. In Southern Mindanao, abaca textiles are characterised by its working with warp ikat patterns combined with the use of natural red and black dyes. Bagobo abaca textiles, or inabal, are particularly noted for the structure and colouring of the garments, their highly polished surface, and elaborate ornamentation using embroidery, beadwork and applique.

Unlike other textile-producing communities in the Philippines who have become known for their ceremonial blankets, the most socially significant textiles made by the Bagobos are their clothing, which are graded according to the gender and status of the wearer. The highest status cloth with the most complex ikat patterns, are made into three-panelled tube skirts or sonnod for women, which were avidly collected by Benedict. She was particularly attracted to the unsewn central panels or “mother” pieces, called ine or ina. She referred to them as panapisan, although the more correct term is ginayan, which means “rendered with an ine/ina.”

Both men and women wear close fitting jackets which are richly patterned with shells, glass beads, and embroidery, though men’s garments are often made of a relatively lower status cloth. Men also wear knee-length trousers called saroar, which are commonly striped and woven with bands on the hems called tutuc. According to Quizon's research, Bagobo traditional belief stipulates that once a man has killed two people, he becomes a magani, a warrior-chief, and is allowed to wear the special red-blood head-kerchief woven by female mabalians. When he kills four, he can wear trousers of the same red-blood colour. And finally, when he takes six lives, he is entitled to wear a full red-blood ensemble. Only maganis and mabalians were traditionally entitled to wear this special cloth, though other women of rank and sons of chiefs were also sometimes given this privilege.

Jewelry and accessories

Bagobo men and women are known for their highly patterned ceremonial clothing. The AMNH collection includes several examples of rings, necklaces, bracelets, and arm and leg bangles made of brass and shells. Notable is the Bagobos’ use of small brass bells that have become a trademark of their traditional wear. Men and women also wear ear plugs connected under the chin by strings of beads. The wealthy wear ear plugs made of ivory imported from Borneo. Women also adorn their hair with plumes and bead-encrusted wooden combs festooned with beads.

Knives and weapons

The principal weapons of the Bagobo hunter and warrior are the knife and spear. An attack begins with the throwing of spears, followed by close combat with the knives. Both men and women have knives, which they carry in decorated sheaths and scabbards. The common utility knife is called a sangi, sometimes referred to as the “woman’s knife,” which is a short blade knife with an up-curving edge. Handles and scabbards come in a variety of materials, including wood, brass and rattan. They are also commonly adorned with the small brass bells. The typical knife for fighting is the kampilan sword, which has a longer straight-edged metal blade.

Bags and baskets

Bagobos weave abaca into a variety of bags for men and women. Men use a flat type of bag worn on their backs, while women carry small trinket bags and pouches. Both are richly adorned with beads, brass bells and other embellishments. Baskets, on the other hand, are commonly made out of bamboo and rattan, though sometimes other materials such as pandan are also used. Bagobos usually employ three variants of weaves in their baskets and a majority of their baskets have surfaces divided into three parallel bands, which are produced by making a slight variation in the weave or by using darkened strips of bamboo or rattan. Special baskets also have decorated bands with shells, beads and other ornaments.

Bamboo tubes

Bagobos use bamboo tubes as containers for food and drinks. During special ceremonies, they make offerings of rice and chicken which have been prepared and placed specifically in bamboo tubes. According to traditional belief, food cooked in pots or other vessels were not considered worthy for the spirits. Like their other crafted objects, the bamboo tubes were intricately incised with decorative lines and many had carrying straps also adorned with shells and beads.

Brass betel nut boxes

The Bagobos were highly skilled in brass founding and casting using the lost wax method, and this is exemplified in their betel nut boxes. They often come in pairs or have different compartments for the betel nut, leaf and powdered lime. The lids are usually applied with fine brass filigree or inlaid with copper, silver or mother-of-pearl. Some boxes are fully decorated on all its sides, with brass chains attached with small bells or even its own cleaning implement.

The Philippine Hall at the AMNH was taken down in the late 1950s and some of its exhibits has since been integrated into the Margaret Mead Hall of Pacific Peoples. The Hall opened in 1984 to showcase the diverse cultures of the Pacific, including Australia, Indonesia, Micronesia, Melanesia, Polynesia, and the Philippines. At present, only 29 artefacts from the Bagobo collection are displayed in the Margaret Mead Hall. This selection of undisplayed material provides an opportunity to view and study this remarkable collection, and offers a glimpse of the rich and unique aesthetic and material culture of the Bagobo people.

* Talisa Chan served as the SOAS Co-creator intern for the Mapping Project for AY 2023.

**The Mapping Project's introduction to the entire AMNH collection is here:

https://philippinestudies.uk/mapping/collections/show/357. This is a small portion of the over 10,000 Philippine materials at the AMNH.

References:

American Museum of Natural History. “Collections from the Philippine Islands.” https://data.library.amnh.org/archives-authorities/id/amnhc_4000011.

Benedict, Laura Watson. A Study of Bagobo Ceremonial, Magic and Myth. (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1916)

Bernstein, Jay H. “The Perils of Laura Watson Benedict: A Forgotten Pioneer in Anthropology,” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, Vol. 26, No. 1-2, March/June 1998: 165-191. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29792415.

Cole, Fay-Cooper. “The Wild Tribes of Davao District, Mindanao,” Publications of the Field Museum of Natural History, Anthropological Series, Vol. 12, No. 2, September 1913: I-VII, 49-203. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29782138.

Hull, Henry Usher. “The Bagobo,” The Museum Journal, Vol. VII, No. 3, 1916. https://www.penn.museum/sites/journal/516/.

Kroeber, Alfred Louis. Peoples of the Philippines. (New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1919)

Quizon, Cherubim A. “Between the field and the museum: the Benedict Collection of Bagobo abaca ikat textiles,” Textile Society of American Symposium Proceedings, 1998. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/201.