19th-century Whitework on Piña

Exhibit Description

Made from the finest fibres of the pineapple leaf, piña is a diaphanous fabric fashionable in 19th-century Philippine colonial society .

The pineapple plant (Ananas comosus or A. sativa), native to Central and South America, was introduced to Asia in the 16th-century by the Portuguese and the Spanish. As early as 1586, (Salazar, 34), the fruits were sent to the Philippines from China. As for pineapple leaves being a source of useful fibres, this was known in India (Boitard, 107), presumably long before it was known in the Philippines. Leaves from similar plants such as maguey and some bromeliads were also valued for their fibres in parts of America (Bailey, 291). In the Philippines, there is mention of woven textiles using natural plant fibres from abaca as early as the seventeenth century. (Castro, 66 )

To date, documentary evidence of textile produced from piña is found no earlier than the nineteenth century, when industrialized countries conducted research on useful fibers around the globe. In 1820 a French expedition to the tropics brought Samuel Perrottet, a horticulturist of the Jardine des Plantes (Paris), to Manila where he discovered piña cloth. Perrotet claimed that the fibres came from a new species of pineapple with long leaves and an excellent fruit. He named it Bromelia pigna (Perrottet, 15).

In the 1840s the French scientist, Jean Mallat, reported from the weaving centre of Iloilo Province that pineapple heads were cut off to encourage wider and longer leaves. Perhaps he was referring to the cultivated pineapple (Mallat, 195). In the 1890’s an author referred to the opinion of Daniel Morris, assistant director of Royal Kew Gardens (London), who stated that the fibre source for piña cloth was a West Indian pineapple naturalized in the Philippines (Parsons, 37). To the American fibres expert, Charles Dodge, it was simply the cultivated pineapple (A. sativa) “in a semi-wild state,” It had a small fruit and leaves that could be 5-6 feet long (Dodge, 58, 96). While reports were either confusing or erroneous, it is very likely that, over the decades, fibres from a variety of pineapple cultivars were tried for weaving piña cloth.

Finally, in 1912, the Philippine Commission under the U.S. government introduced 2,000 plants of Hawaiian pineapple and 1,000 of Red Spanish pineapple. Until today the Red Spanish cultivar, or what is called Native Philippine Red, is used by the piña fibre industry in Aklan Province (United States 1912, 243; Pineapple Production Guide).

The processing and weaving of piña fibres are completely done manually until today. A pot shard is used to scrape fibres from the leaves. (Decortication machines are only effective for harvesting coarse fibres). After a process of washing, cleaning, drying, and combing, fibres are sorted and the finest ones are reserved for weaving. As in the preparation of weaving fibres of abaca by indigenous Filipinos, piña fibres are knotted end to end using the fingers and a small bamboo blade. On the loom, the fabric is woven in plain weave and may be decorated with brocading or striping.

Brocading, or the application of supplementary weft patterns, is a traditional technique commonly used in Southeast Asian weaving communities. It is known as suksuk (or sinuksuk) in the Philippines and usually applied to piña with cotton yarns.

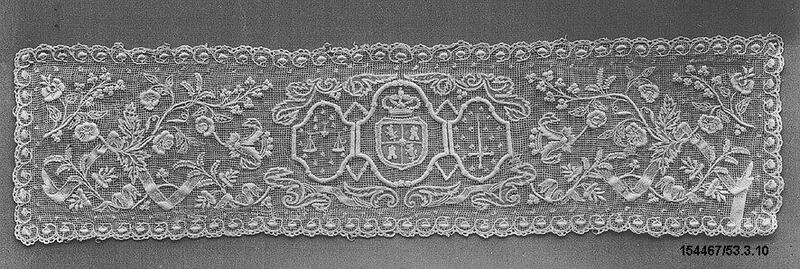

In the nineteenth century, finished piña cloth was sent to Manila and its surrounding areas for embroidery, calado (openwork) or sombrado (shadow work). The most impressive form of calado on piña cloth was drawn thread work.

"The Spanish arms and the symbols of Law and Justice suggest that these sleeve pieces were worn by an official of the law-courts during the Spanish occupation of the Philippine Islands.” (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/227614/

accessed 12.26.20)

This technique involves cutting off selected warp and weft yarns of the fabric to create open areas and reinforcing these areas with decorative stitches. Its resemblance to lace or delicate tulle, which was produced mechanically in Europe, made it particularly appealing to upper-class women in colonial society. On kerchiefs, drawn thread work was used to create net-like borders or fillings for embroidered vegetal forms.

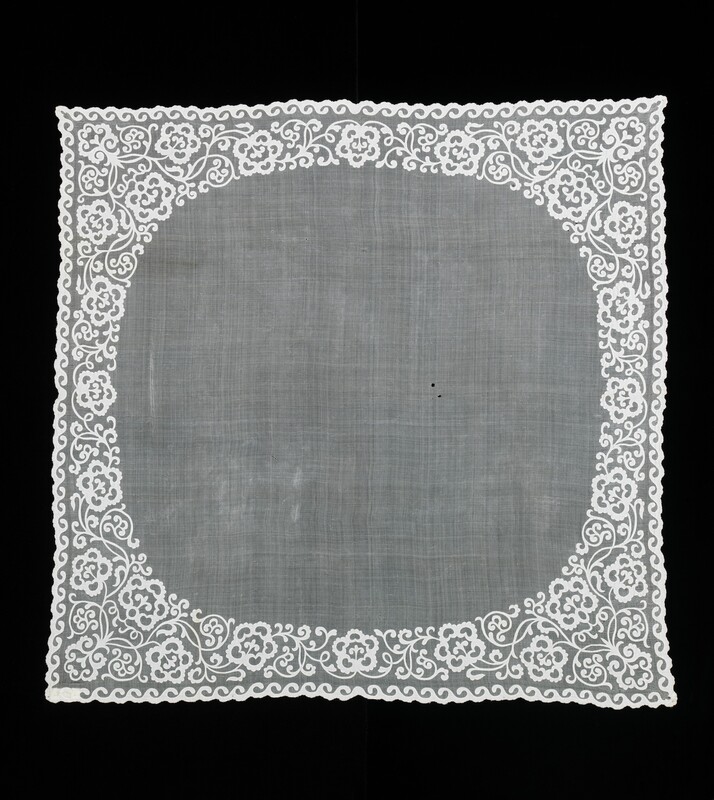

Sombrado (shadow work) in the form of appliqué was another technique that was applied to piña. Vegetal forms and scrolling vines were cut out from cotton fabric and attached to the reverse side of the fabric to create a silhouette effect.

European forms of needlework were formally taught in the Philippines through orphanages and girls’ schools run by religious orders. However, in the 1840’s, both male and female from the village of Malate worked on calado embroidery. Members of a French mission visiting Manila noted the large number of Tagalog workers in the best embroidery factories (Mallat, 459; Salmon, 62). In the barrio of Looban, Paco (a suburb of Manila), a native member of the Sisters of Charity founded an orphanage called Asilo de San Vicente de Paul. From the 1880’s until the early 1900’s the Asilo became well-known for the excellent embroidery work produced by young girls (Girls’ Schools in Manila and the Provinces, 310-312).

The designs and needlework techniques that were applied to piña cloth belong to the genre of whitework that is interpreted in various ways around the globe. While it was mainly associated with clothing and accessories in 19th-century Philippine colonial society, it was also developed for the Western market. It was applied to piña table runners, kerchiefs, handkerchiefs, collars, children’s clothing, and other accessories. Examples of piña material as used by Filipinos, as well as those made for export or the tourist market, are well-represented in museums of the Philippines, Europe and the United States.

__________

REFERENCES:

Bailey, L.H. Cyclopedia of American Agriculture: A Popular Survey of Agricultural Conditions, Practices and Ideals in the United States and Canada, Vol. 2, 3rd ed. New York: Macmillan Co., 1911.

Boitard, Pierre. Nouveau manuel du cordier: contenant l’histoire et la culture de toutes les plantes textiles, les diverses méthodes de rouissage et d'extraction de la filasse, la fabrication de toutes sortes de cordes, etc. Paris: Librairie encyclopédique de Roret, 1839.

Castro, Sandra B. 2018. Textiles in the Philippine colonial landscape: a lexicon and historical survey. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press,.

Dodge, Charles R. A Descriptive Catalogue of Useful Fiber Plants of the World Including the Structural and Economic Classifications of Fibers. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1897.

“Girls’ Schools in Manila and the Provinces,” in The Philippine Islands, vol. 5, 304-314.

Mallat de Bassilan, Jean Baptiste, and Pura Santillan Castrence (trans.). The Philippines. Manila: National Historical Institute, 1983.

Parsons, Charles W. 1895. The Fibre Bearing Plants of Florida. Being a Description of the Agave sisalana sansivieria, Bromelia sylvestris, Pineapple, Urena lobata and Ramie Plants. Together with Methods of Propagation, Cultivation and Extraction of the Fibres. Savannah: The Morning News Print, 1895. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/80329#page/3/mode/1up (accessed 12/30/2020).

Perrottet, Samuel. Catalogue raisonné des plantes introduites dans les colonies françaises de Bourbon et de Cayenne, et de celles rapportées vivantes des mers d'Asie et de la Guyane au jardin du Roi à Paris. Paris: Impr. de Lebel, 1824. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k64713451

(accessed 12.20.20)

“Pineapple Production Guide”, Agriculture Monthly (Sept 5, 2019).

https://www.agriculture.com.ph/2019/09/05/pineapple-production-guide/ (accessed 12.20.20).

Salazar, Domingo and others, “Relation of the Philipinas Islands,” in The Philippine Islands, vol. 7, 29-51.

United States. Annual Reports of the War Department for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1906, Vol. 9, Report of the Philippine Commission. Part 3. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1907.

United States. Report of the Philippine Commission to the Secretary of War. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912.

https://bit.ly/35HPSVx (accessed 1/5/2021).

Explore items in Exhibit

Collar made of Piña

Bertha. The production of pineapple cloth is specific to the Philippines ,China* and West Indies. Woven by hand from the leaf fiber of the pineapple plant, and embellished with intircate embroidery, this highly valued fabric was fashioned into…

Collar Made from pineapple fibre

Collar of pineapple fibre embroidered in cotton and bobbin lace. Sheer fabric embroidered in white cotton in satin, stem, buttonhole and drawn fabric stitches with eyelet holes. Each side is decorated with a wavy trailing stem from which grow,…

Pineapple Fabric or Textile ( Piña)

Square doily of piña cloth with brocaded pattern of floral motifs around a center circle. Piña (pineapple) fiber.

Pineapple Fibre Handkerchief

Handkerchief of pineapple fibre, with white cotton embroidery and drawn work. The middle is plain except for the initials 'J.Y. de M'. There is an inner border of rose stems tied by ribbons. The space beyond is closely covered with small dots, and…